What happened in

East Germany?

Julia E. Ault

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY

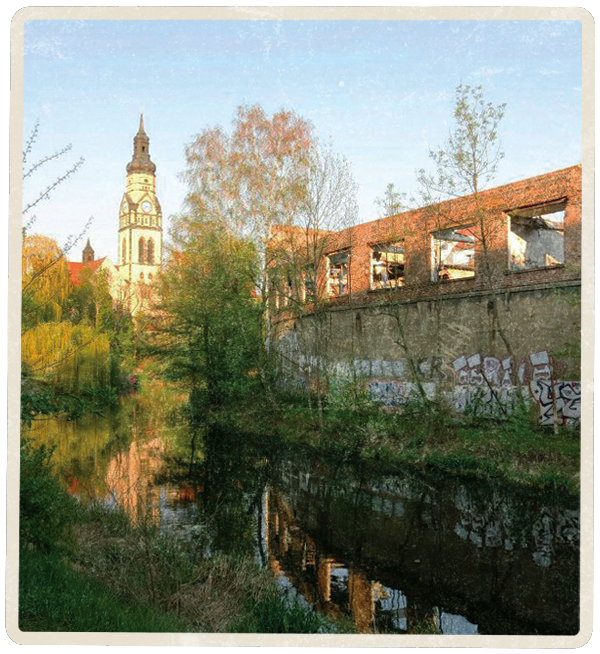

▲ A section of the Berlin Wall on Harzer Strasse, Germany, October 1962

On November 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, and so the story goes, communism came to an end in Europe. A symbol of oppression since its construction in 1961, the Berlin Wall continues to be used as a shorthand for the Cold War, especially in Europe.

The Wall invokes images and memories of the standoff between the two superpowers and their proxies, East and West Germany. Tales of secret passages and desperate attempts to cross the heavily militarized border remain a fixture in popular culture.

The actual opening of the Wall in 1989 was a rather inglorious moment, though, because East German authorities accidentally announced new policies over the radio before informing border police. East Germans heard the news and flooded the checkpoints, demanding to cross into the democratic and capitalist West Germany. Lacking instructions to the contrary, officials relented. In Berlin, people from East and West climbed the fortifications and celebrated. Newscasters from around the world, including well-known NBC anchor Tom Brokaw, heralded the events as the historic moment that brought East Germans freedom.

The fall of the Wall is a well-known story. But what came next? Diplomatically, we know that the Cold War ended in Europe, the Red Army pulled out of East Germany, and Germany was united. But on a societal level, how did 17 million East Germans react to the myriad of changes they confronted in a new democratic and capitalist world?

To understand the magnitude of these transformations, we must first consider what life was like under communism. East Germans experienced repression; faced imprisonment for any number of crimes against the state, including attempting to flee to the West; and lived in the shadow of one of the most extensive surveillance apparatuses of the time. They had fewer consumer goods than their West German counterparts, and obviously, experienced enormous challenges if they wished to travel outside of the Soviet bloc. At the same time, East Germans went about their lives. They attended school, they went to work, they had families, they celebrated birthdays and weddings. East Germans lived in a restricted societal and political system, but they were humans—not automatons.

As communism collapsed in the fall of 1989, East Germans took to the streets to demand freedoms that they had been denied. They demanded reform, including the right to travel; the right to multiple, legitimate, and independent political parties (democracy); a clean environment; and better access to consumer goods. With the opening of the border on November 9, East Germans felt a sense of euphoria. They could now access the many things that they had desired but been forbidden. As the protests went on, public sentiment changed from calling for reform of East Germany to unification with West Germany. On October 3, 1990, a single, unified Federal Republic of Germany came into being and East Germany disappeared.

The months and years that followed present a complicated story of excitement, bewilderment, and disillusionment. Overnight, institutions and certainties that East Germans expected were gone.

McDonalds opened locations across the former communist territory, new shopping malls sprang up in fields, and bright, colorful clothing became the norm. The influx of goods brought excitement, but many East German industries failed to transition to a competitive market economy. Quickly, jobs disappeared, and unemployment rose. Workers of all ages were confronted with uncertain futures. Many young people left the former East Germany, searching for better jobs and more opportunity in the West. East German families, accustomed to universal, state-run daycare, had to find new childcare arrangements that inevitably cost more. Politically, East Germans struggled to navigate an unfamiliar system that was already well-established and typically run by West Germans.

The dual transition (to democracy and capitalism from communist dictatorship) also presented unexpected challenges. In the case of environmental protection, for

example, German unification brought in substantial investments for pollution abatement. Additionally, antiquated industries that dumped waste into rivers and released sulfur dioxide into the air did not survive privatization or became subject to more stringent regulation. Renewal projects cleaned up towns and turned old open-cast mines into beautiful lakes. For the environment, the transition was an absolute win. The new boardwalks, parks, and swimming areas, however, are often empty as a result

of outmigration over the last three decades. The air was clean, but no one was left to breathe it. Massive federal support could not fully offset differences in living standards, job opportunities, and outlooks on life between the former East and West Germany. Those shopping malls built in the 1990s have closed again in light of depopulation and unemployment, leaving abandoned buildings and even fewer options for those who remain. Now, over thirty years later, the gap is closing, but disparities continue.

“

Meaningful transformation takes a long time and almost inevitably has unexpected consequences.

Disenchantment with life after communism has led some former East Germans to turn to a nostalgia for the East (In German: Ostalgie = Ost + Nostalgie). They imagine that everything was better under communism: consumer goods were cheaper, crime was virtually nonexistent, jobs were guaranteed by the state. Some also blur the lines between reminiscing about their youths and the political system in which they occurred. Whether or not truly invested in East Germany’s socialist project, this nostalgia illuminates what former East Germans see as the failings of Germany today. The excitement and anticipation of 1989 has been tempered over time.

What can we take away from this narrative of political and societal transformation? First, meaningful transformation takes a long time and

almost inevitably has unexpected consequences. Even much desired transitions can prove problematic, especially when polices come from the top-down without community support or input. Second, nostalgia for an imaged past is a powerful force. Few East Germans would actually wish a return to communism but invoking certain aspects of the previous regime can be used to criticize the existing system. Third, and finally, it is easy to lose sight of the individual in moments of largescale transformation. Individual transitions are at stake, too, with significant financial, emotional, and psychological consequences. Acknowledging complex human experiences is essential to maintaining empathy, historical and contemporary.

What happened in

East Germany?

Julia E. Ault

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY

On November 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, and so the story goes, communism came to an end in Europe. A symbol of oppression since its construction in 1961, the Berlin Wall continues to be used as a shorthand for the Cold War, especially in Europe.

The Wall invokes images and memories of the standoff between the two superpowers and their proxies, East and West Germany. Tales of secret passages and desperate attempts to cross the heavily militarized border remain a fixture in popular culture.

The actual opening of the Wall in 1989 was a rather inglorious moment, though, because East German authorities accidentally announced new policies over the radio before informing border police. East Germans heard the news and flooded the checkpoints, demanding to cross into the democratic and capitalist West Germany. Lacking instructions to the contrary, officials relented. In Berlin, people from East and West climbed the fortifications and celebrated. Newscasters from around the world, including well-known NBC anchor Tom Brokaw, heralded the events as the historic moment that brought East Germans freedom.

The fall of the Wall is a well-known story. But what came next? Diplomatically, we know that the Cold War ended in Europe, the Red Army pulled out of East Germany, and Germany was united. But on a societal level, how did 17 million East Germans react to the myriad of changes they confronted in a new democratic and capitalist world?

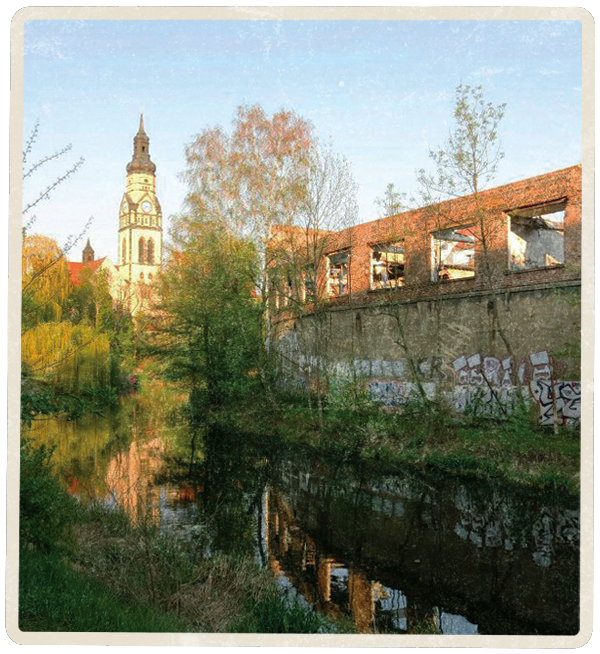

▲ A section of the Berlin Wall

Harzer Strasse, Germany, October 1962

To understand the magnitude of these transformations, we must first consider what life was like under communism. East Germans experienced repression; faced imprisonment for any number of crimes against the state, including attempting to flee to the West; and lived in the shadow of one of the most extensive surveillance apparatuses of the time. They had fewer consumer goods than their West German counterparts, and obviously, experienced enormous challenges if they wished to travel outside of the Soviet bloc. At the same time, East Germans went about their lives. They attended school, they went to work, they had families, they celebrated birthdays and weddings. East Germans lived in a restricted societal and political system, but they were humans—not automatons.

“

Meaningful transformation takes a long time and almost inevitably has unexpected consequences.

As communism collapsed in the fall of 1989, East Germans took to the streets to demand freedoms that they had been denied. They demanded reform, including the right to travel; the right to multiple, legitimate, and independent political parties (democracy); a clean environment; and better access to consumer goods. With the opening of the border on November 9, East Germans felt a sense of euphoria. They could now access the many things that they had desired but been forbidden. As the protests went on, public sentiment changed from calling for reform of East Germany to unification with West Germany. On October 3, 1990, a single, unified Federal Republic of Germany came into being and East Germany disappeared.

The months and years that followed present a complicated story of excitement, bewilderment, and disillusionment. Overnight, institutions and certainties that East Germans expected were gone. McDonalds opened locations across the former communist territory, new shopping malls sprang up in fields, and bright, colorful clothing became the norm. The influx of goods brought excitement, but many East German industries failed to transition to a competitive market economy. Quickly, jobs disappeared, and unemployment rose. Workers of all ages were confronted with uncertain futures. Many young people left the former East Germany, searching for better jobs and more opportunity in the West. East German families, accustomed to universal, state-run daycare, had to find new childcare arrangements that inevitably cost more. Politically, East Germans struggled to navigate an unfamiliar system that was already well-established and typically run by West Germans.

The dual transition (to democracy and capitalism from communist dictatorship) also presented unexpected challenges. In the case of environmental protection, for example, German unification brought in substantial investments for pollution abatement. Additionally, antiquated industries that dumped waste into rivers and released sulfur dioxide into the air did not survive privatization or became subject to more stringent regulation. Renewal projects cleaned up towns and turned old open-cast mines into beautiful lakes. For the environment, the transition was an absolute win. The new boardwalks, parks, and swimming areas, however, are often empty as a result of outmigration over the last three decades. The air was clean, but no one was left to breathe it. Massive federal support could not fully offset differences in living standards, job opportunities, and outlooks on life between the former East and West Germany. Those shopping malls built in the 1990s have closed again in light of depopulation and unemployment, leaving abandoned buildings and even fewer options for those who remain. Now, over thirty years later, the gap is closing, but disparities continue.

Disenchantment with life after communism has led some former East Germans to turn to a nostalgia for the East (In German: Ostalgie = Ost + Nostalgie). They imagine that everything was better under communism: consumer goods were cheaper, crime was virtually nonexistent, jobs were guaranteed by the state. Some also blur the lines between reminiscing about their youths and the political system in which they occurred. Whether or not truly invested in East Germany’s socialist project, this nostalgia illuminates what former East Germans see as the failings of Germany today. The excitement and anticipation of 1989 has been tempered over time.

What can we take away from this narrative of political and societal transformation? First, meaningful transformation takes a long time and almost inevitably has unexpected consequences. Even much desired transitions can prove problematic, especially when polices come from the top-down without community support or input. Second, nostalgia for an imaged past is a powerful force. Few East Germans would actually wish a return to communism but invoking certain aspects of the previous regime can be used to criticize the existing system. Third, and finally, it is easy to lose sight of the individual in moments of largescale transformation. Individual transitions are at stake, too, with significant financial, emotional, and psychological consequences. Acknowledging complex human experiences is essential to maintaining empathy, historical and contemporary.