(Ir)responsible Rhetoric

& Cultural Transformation

Kendall Gerdes

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF WRITING & RHETORIC

When I joined the faculty in the Department of Writing & Rhetoric Studies one year ago, I had some trepidation about teaching intermediate writing (WRTG 2010) in an election year. In the fall of 2016, I had been a new assistant professor teaching professional writing at Texas Tech University in Lubbock, Texas, a city that had been deemed “second most conservative” (actually, right behind Provo, Utah!) back in 2005. The results of the 2016 election left me stunned and I felt I had no choice about how to teach my classes that week but to share my disappointment with my students. I framed a lesson about the limits of professionalism, the point at which professionalism fails and falls apart. I told my students that day in part:

Jacob Tobia writes that “Professionalism is a funny term, because it masquerades as neutral despite being loaded with immense oppression. As a concept, professionalism is racist, sexist, homophobic, transphobic, classist, imperialist and so much more—and yet people act like professionalism is non-political” (2014). As a teacher of professional writing, I have struggled all semester with whether and how to engage you in the politics of professionalism, especially in an election season that pitted professional politics against the violation of American political norms in an unprecedented way.

Four years later, many of us, I’d wager, felt all too familiar with the dissolution of American political norms. I resolved to approach the teaching of required writing classes (like the one I taught in the fall of 2020) with certain disciplinary values front and center. As a rhetorician, my areas of research and expertise include how the way we argue about public issues can cause harm. By harm I mean both symbolic violence, yes, but also “real,” material harm in actual people’s lives. I wanted to be sure that I gave my students the chance to understand this viewpoint, even if they don’t share it.

So I now begin my intermediate writing course with four weeks reading Patricia Roberts-Miller’s brief and elegant gem of a book, Demagoguery and Democracy (2017). Roberts-Miller argues that “demagoguery” describes a highly polarized form of argumentation in which a focus on policy is supplanted by a focus on identity. Whether a speaker (or writer —a rhetor) is a member of one’s in-group matters more than whether they are proposing a feasible plan that will solve a real problem. Certainty in one’s convictions— and that one’s own perception of reality is universal and unmediated (a belief called “naïve realism”)—ensures that arguments about the complexity or nuance of a political situation fall flat. Contrasts are exaggerated so that everything can be viewed in black and white; phrased in terms of “us” versus “them.”

So far in my experience teaching Roberts-Miller’s book, students are pleasantly surprised by the invitation to think about writing and rhetoric in terms that give them purchase on the rhetorical culture of their communities, be it American national politics or their families, workplace, favorite sports teams, or fandoms. My guess is that many students import their expectations of college writing from experiences in high school that lead them to think of writing as a difficult and unpleasant task, a recitation of knowledge rather than a way of exploring and thinking. It is a delight to be a part of a department and college that instead shares an esteem for writing as a method of inquiry, of reflecting on what persuades us and on how the quality of our deliberation and decision-making can be made better.

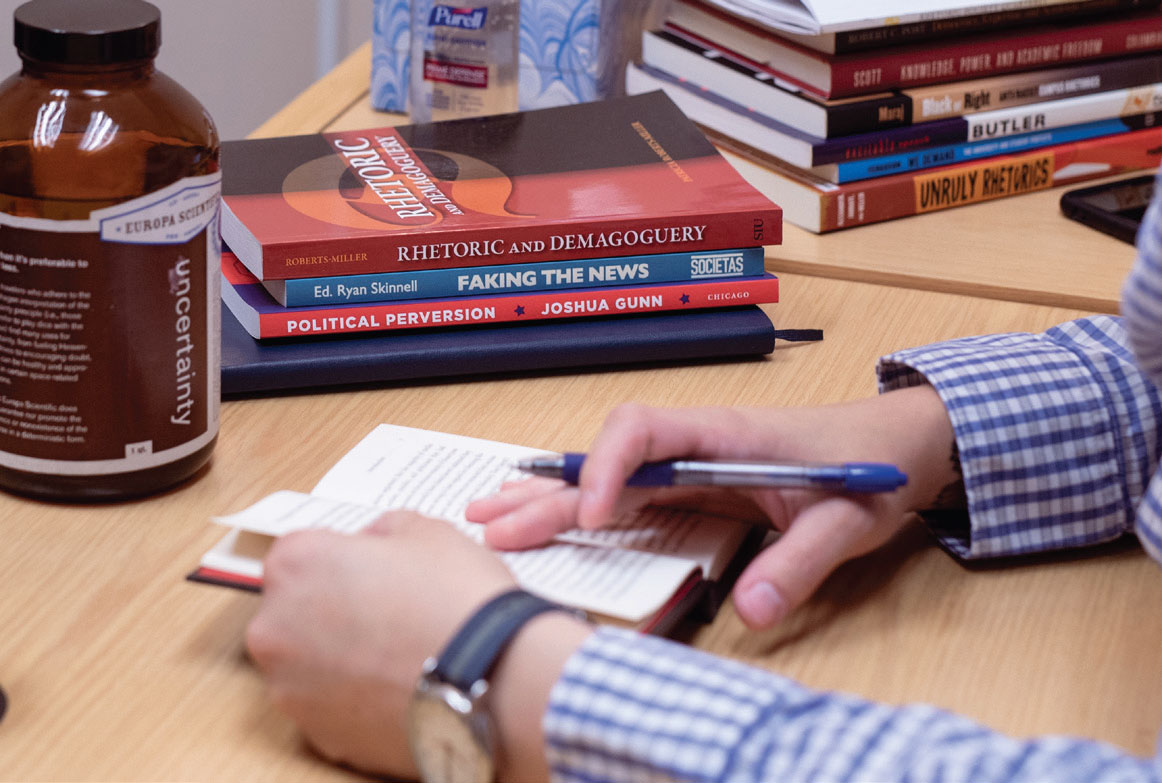

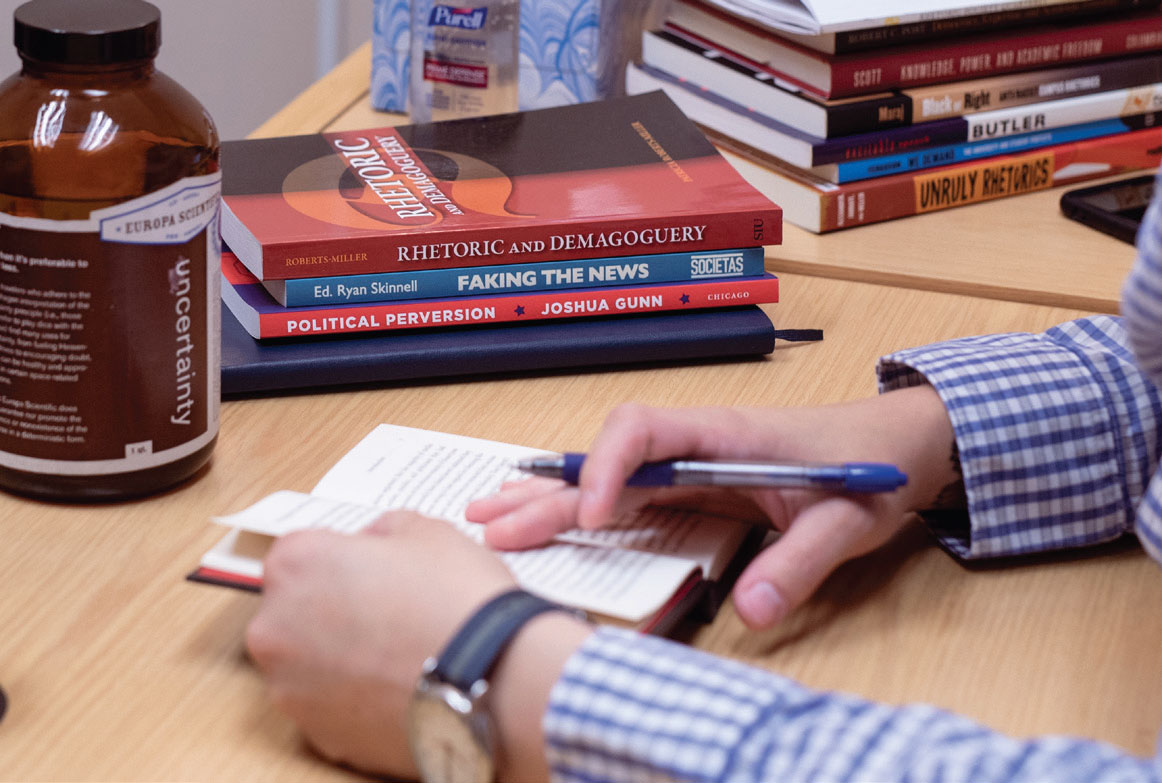

Rhetoricians from multiple disciplines have been working on the problem of demagoguery, and the way it depends on a culture that tolerates it rather than a few charismatic individuals who wield it: Roberts-Miller published an extended scholarly version of her argument in Rhetoric and Demagoguery (Southern Illinois University Press, 2019). Joshua Gunn published Political Perversion: Rhetorical Aberration in the Time of Trumpeteering (The University of Chicago, 2020). Ryan Skinnell edited a collection of essays called Faking the News: What Rhetoric Can Teach Us About Donald J. Trump (Imprint Academic, 2018). The critical insights of these scholars go beyond passing judgment on individual demagogues (however powerful) to analyzing the social conditions and media ecologies that support them. In Rhetoric and Demagoguery, Roberts-Miller argues that the ability of demagoguery to cause harm can be curbed when the culture that supports it changes. That means the responsibility for an ethical rhetorical culture is one we bear collectively.

I think teaching students about demagoguery gives them a language to think about ethical argumentation and democratic conflict, which is to say, about how to negotiate disagreements with people who are different from you. These questions are often centered in the stories we tell ourselves in my discipline about rhetorical history and its relationship to democracy. And at this moment in rhetorical history and in American political history, the language of rhetorical ethics is needed for us to embrace our collective responsibility and encourage those in our spheres of influence to value difference, to argue fairly and inclusively when we disagree, and to entertain the possibility of changing our minds.

Yet, remembering Tobia’s caution about the apparent neutrality of professionalism, with its hidden norms favoring the already privileged and powerful, my recourse above to the collective pronouns “we” and “us” could conceal the exclusion of dissent necessary to support the fiction that everybody in a democracy has a voice. Not every voice has equal rhetorical power. Not every person is seen as a citizen, and even my own beliefs create ideological blindspots about who I can recognize as capable of rhetorical engagement. What I’m saying is that responsible rhetoric is a practice, but it’s also a calling: To keep moving beyond what is given and insist that the culture transforms.

(Ir)responsible Rhetoric & Cultural Transformation

Kendall Gerdes

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF WRITING & RHETORIC

When I joined the faculty in the Department of Writing & Rhetoric Studies one year ago, I had some trepidation about teaching intermediate writing (WRTG 2010) in an election year. In the fall of 2016, I had been a new assistant professor teaching professional writing at Texas Tech University in Lubbock, Texas, a city that had been deemed “second most conservative” (actually, right behind Provo, Utah!) back in 2005. The results of the 2016 election left me stunned and I felt I had no choice about how to teach my classes that week but to share my disappointment with my students. I framed a lesson about the limits of professionalism, the point at which professionalism fails and falls apart. I told my students that day in part:

Jacob Tobia writes that “Professionalism is a funny term, because it masquerades as neutral despite being loaded with immense oppression. As a concept, professionalism is racist, sexist, homophobic, transphobic, classist, imperialist and so much more—and yet people act like professionalism is non-political” (2014). As a teacher of professional writing, I have struggled all semester with whether and how to engage you in the politics of professionalism, especially in an election season that pitted professional politics against the violation of American political norms in an unprecedented way.

Four years later, many of us, I’d wager, felt all too familiar with the dissolution of American political norms. I resolved to approach the teaching of required writing classes (like the one I taught in the fall of 2020) with certain disciplinary values front and center. As a rhetorician, my areas of research and expertise include how the way we argue about public issues can cause harm. By harm I mean both symbolic violence, yes, but also “real,” material harm in actual people’s lives. I wanted to be sure that I gave my students the chance to understand this viewpoint, even if they don’t share it.

So I now begin my intermediate writing course with four weeks reading Patricia Roberts-Miller’s brief and elegant gem of a book, Demagoguery and Democracy (2017). Roberts-Miller argues that “demagoguery” describes a highly polarized form of argumentation in which a focus on policy is supplanted by a focus on identity. Whether a speaker (or writer —a rhetor) is a member of one’s in-group matters more than whether they are proposing a feasible plan that will solve a real problem. Certainty in one’s convictions— and that one’s own perception of reality is universal and unmediated (a belief called “naïve realism”)—ensures that arguments about the complexity or nuance of a political situation fall flat. Contrasts are exaggerated so that everything can be viewed in black and white; phrased in terms of “us” versus “them.”

So far in my experience teaching Roberts-Miller’s book, students are pleasantly surprised by the invitation to think about writing and rhetoric in terms that give them purchase on the rhetorical culture of their communities, be it American national politics or their families, workplace, favorite sports teams, or fandoms.

My guess is that many students import their expectations of college writing from experiences in high school that lead them to think of writing as a difficult and unpleasant task, a recitation of knowledge rather than a way of exploring and thinking. It is a delight to be a part of a department and college that instead shares an esteem for writing as a method of inquiry, of reflecting on what persuades us and on how the quality of our deliberation and decision-making can be made better.

Rhetoricians from multiple disciplines have been working on the problem of demagoguery, and the way it depends on a culture that tolerates it rather than a few charismatic individuals who wield it: Roberts-Miller published an extended scholarly version of her argument in Rhetoric and Demagoguery (Southern Illinois University Press, 2019). Joshua Gunn published Political Perversion: Rhetorical Aberration in the Time of Trumpeteering (The University of Chicago, 2020). Ryan Skinnell edited a collection of essays called Faking the News: What Rhetoric Can Teach Us About Donald J. Trump (Imprint Academic, 2018). The critical insights of these scholars go beyond passing judgment on individual demagogues (however powerful) to analyzing the social conditions and media ecologies that support them. In Rhetoric and Demagoguery, Roberts-Miller argues that the ability of demagoguery to cause harm can be curbed when the culture that supports it changes. That means the responsibility for an ethical rhetorical culture is one we bear collectively.

I think teaching students about demagoguery gives them a language to think about ethical argumentation and democratic conflict, which is to say, about how to negotiate disagreements with people who are different from you. These questions are often centered in the stories we tell ourselves in my discipline about rhetorical history and its relationship to democracy. And at this moment in rhetorical history and in American political history, the language of rhetorical ethics is needed for us to embrace our collective responsibility and encourage those in our spheres of influence to value difference, to argue fairly and inclusively when we disagree, and to entertain the possibility of changing our minds.

“

Certainty in one’s convictions— and that one’s own perception of reality is universal and unmediated (a belief called “naïve realism”)—ensures that arguments about the complexity or nuance of a political situation fall flat. Contrasts are exaggerated so that everything can be viewed in black and white; phrased in terms of “us” versus “them.”

Yet, remembering Tobia’s caution about the apparent neutrality of professionalism, with its hidden norms favoring the already privileged and powerful, my recourse above to the collective pronouns “we” and “us” could conceal the exclusion of dissent necessary to support the fiction that everybody in a democracy has a voice. Not every voice has equal rhetorical power. Not every person is seen as a citizen, and even my own beliefs create ideological blindspots about who I can recognize as capable of rhetorical engagement. What I’m saying is that responsible rhetoric is a practice, but it’s also a calling: To keep moving beyond what is given and insist that the culture transforms.