The Presidency in Transition

Kevin Coe

PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION

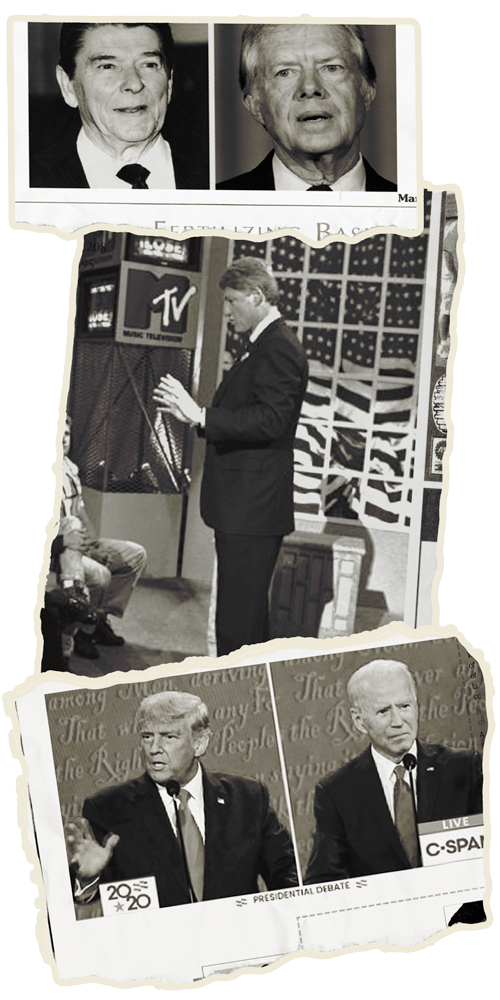

Few things signal change so clearly in the U.S. as an incumbent president losing reelection. These rare moments—there have been just three in the last 40 years—invite the public to imagine sharp contrasts between what was and what will be. Jimmy Carter’s national “malaise” became Ronald Reagan’s “shining city on a hill.” George H. W. Bush’s reserved traditionalism was replaced by Bill Clinton and the “New Democrats.”Donald Trump’s chaotic populism gave way reluctantly, even violently, to Joe Biden’s pleas for unity.

These dramatic moments of transition are easy to spot because they happen quickly and focus on individuals. One president replaces another. One administration is in, the other is out. But what about broader transitions that shape the institution these people represent? What about changes to the presidency itself?

Those changes are more subtle but just as consequential. Instead of happening between Election Day and Inauguration Day, they happen over the course of terms and decades and eras. For most of my career, I have studied the U.S. presidency in transition. Recently, along with professor Joshua Scacco at the University of South Florida, I have been chronicling the rise of

the “ubiquitous presidency.” The term ubiquity indicates that, increasingly, presidents seem to be everywhere. Whereas Americans in the mid- to late-20th century were accustomed to hearing from presidents mostly about serious topics and in formal settings, such as a scripted speech or a news segment, presidents now show up in a variety of nontraditional spaces, blending the political and nonpolitical in their messages.

What changed? The contexts in which presidents attempt to achieve their primary communicative goals. Modern presidents have always sought visibility via whatever media are available to them. They have always prioritized adaptation as new circumstances arise. And they have always sought to control the information environment as much as possible.

Presidents do not work to achieve these goals in a vacuum, however. They do so within specific contexts that create opportunities and constraints. As those contexts have morphed over time, so too have the strategies presidents use to achieve their enduring goals. Three contexts have shaped the presidency in especially important ways over the past several decades.

● ● ●

The first is the massive increase in the accessibility of information. As cable television and eventually the internet replaced broadcast television as the dominant form of information transmission, Americans had more choices about what content to select. They often didn’t select serious political information, opting instead to be entertained. This forced presidents to work harder to garner the attention they once took for granted. They did so, in part, by following audiences into nontraditional spaces. That’s why Bill Clinton gave multiple interviews to MTV, and why George W. Bush spoke to ESPN’s Sunday Night Baseball. It’s why Barack Obama appeared on the satirical online program Between Two Ferns, and why Donald Trump tweeted out his Emmy Awards rendition of the musical “Oklahoma.” It’s also why one of President Biden’s most widely seen messages of his presidency thus far came as part of the NFL’s Super Bowl halftime show in February. These spaces are where the audiences are.

The second context shaping the presidency is the personalization of politics. As political content found its way into a wider array of venues, the boundary between the political and the personal began to blur. Presidents are increasingly expected to communicate personally and informally. They are asked not just to make a joke but, if the moment calls for it, to be the joke. This transition has its roots in presidential campaigns—think of Richard Nixon appearing on the comedy program Laugh-In in 1968, for example—but didn’t really take off in the presidency itself until the 1990s. A defining moment in this shift occurred when Bill Clinton went on MTV’s Enough is Enough town-hall forum in 1994. There primarily to talk about gun control, Clinton was asked about personal topics as well. Most famously, 17- year-old Laetitia Thompson posed this question: “The world is dying to know—is it boxers or briefs?” Chuckling, Clinton replied: “Usually briefs.” And, recognizing the norm-breaking moment, he followed up: “I can’t believe she did that.” Presidents would have many such personal moments in subsequent decades.

A final context influencing the presidency is pluralism. America has grown dramatically more diverse over the past several decades, both in terms of sheer demographics and in the extent to which issues of inclusion and equity circulate in public discussion. For presidents, these shifts provide two very different rhetorical possibilities. One approach is to embrace the nation’s changing contours, speaking more with and about minority communities. This was the approach Clinton, George W. Bush, and Obama took. For instance, each of these presidents gave more interviews than had their predecessors to media organizations that primarily reached minority communities, and they also talked much more about diversity than had been common in the presidency to that point. Trump took quite a different

approach, leveraging pluralism to stoke fear and play upon prejudices. In one prominent example, Trump tweeted that four members of Congress collectively known as “The Squad”—Alexandria Ocasio- Cortez, Ilhan Omar, Ayanna Pressley, and Rashida Tlaib—should “go back” to “the totally broken and crime infested places from which they came.” Apart from having his facts wrong (all except Omar were born in the U.S.), it was impossible to ignore that Trump had specifically called out four women of color, including the first two Muslim women ever elected to Congress. Trump’s language was a far cry from the last Republican president, George W. Bush, who routinely talked about how Muslims, like people of any other faith or no faith at all, were “equally American.”

Change is inevitable in an institution as complex as the presidency. As the Biden administration approaches the end of its first year, it is already clear that it represents a departure from numerous aspects of the Trump administration. But amid those differences, one thing remains constant: Biden, like all his recent predecessors, will need to respond to the contexts that define the ubiquitous presidency.

◀ The Ubiquitous Presidency, by Joshua M. Scacco and Kevin Coe, examines the intricate relationship between the president, news media, and the public.

The Presidency in Transition

Kevin Coe

PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION

Few things signal change so clearly in the U.S. as an incumbent president losing reelection. These rare moments—there have been just three in the last 40 years—invite the public to imagine sharp contrasts between what was and what will be. Jimmy Carter’s national “malaise” became Ronald Reagan’s “shining city on a hill.” George H. W. Bush’s reserved traditionalism was replaced by Bill Clinton and the “New Democrats.”Donald Trump’s chaotic populism gave way reluctantly, even violently, to Joe Biden’s pleas for unity.

These dramatic moments of transition are easy to spot because they happen quickly and focus on individuals. One president replaces another. One administration is in, the other is out. But what about broader transitions that shape the institution these people represent? What about changes to the presidency itself?

Those changes are more subtle but just as consequential. Instead of happening between Election Day and Inauguration Day, they happen over the course of terms and decades and eras. For most of my career, I have studied the U.S. presidency in transition. Recently, along with professor Joshua Scacco at the University of South Florida, I have been chronicling the rise of the “ubiquitous presidency.” The term ubiquity indicates that, increasingly, presidents seem to be everywhere. Whereas Americans in the mid- to late-20th century were accustomed to hearing from presidents mostly about serious topics and in formal settings, such as a scripted speech or a news segment, presidents now show up in a variety of nontraditional spaces, blending the political and nonpolitical in their messages.

What changed? The contexts in which presidents attempt to achieve their primary communicative goals. Modern presidents have always sought visibility via whatever media are available to them. They have always prioritized adaptation as new circumstances arise. And they have always sought to control the information environment as much as possible.

Presidents do not work to achieve these goals in a vacuum, however. They do so within specific contexts that create opportunities and constraints. As those contexts have morphed over time, so too have the strategies presidents use to achieve their enduring goals. Three contexts have shaped the presidency in especially important ways over the past several decades.

The first is the massive increase in the accessibility of information. As cable television and eventually the internet replaced broadcast television as the dominant form of information transmission, Americans had more choices about what content to select. They often didn’t select serious political information, opting instead to be entertained. This forced presidents to work harder to garner the attention they once took for granted. They did so, in part, by following audiences into nontraditional spaces. That’s why Bill Clinton gave multiple interviews to MTV, and why George W. Bush spoke to ESPN’s Sunday Night Baseball. It’s why Barack Obama appeared on the satirical online program Between Two Ferns, and why Donald Trump tweeted out his Emmy Awards rendition of the musical “Oklahoma.” It’s also why one of President Biden’s most widely seen messages of his presidency thus far came as part of the NFL’s Super Bowl halftime show in February. These spaces are where the audiences are.

The second context shaping the presidency is the personalization of politics. As political content found its way into a wider array of venues, the boundary between the political and the personal began to blur. Presidents are increasingly expected to communicate personally and informally. They are asked not just to make a joke but, if the moment calls for it, to be the joke. This transition has its roots in presidential campaigns—think of Richard Nixon appearing on the comedy program Laugh-In in 1968, for example—but didn’t really take off in the presidency itself until the 1990s. A defining moment in this shift occurred when Bill Clinton went on MTV’s Enough is Enough town-hall forum in 1994. There primarily to talk about gun control, Clinton was asked about personal topics as well. Most famously, 17- year-old Laetitia Thompson posed this question: “The world is dying to know—is it boxers or briefs?” Chuckling, Clinton replied: “Usually briefs.” And, recognizing the norm-breaking moment, he followed up: “I can’t believe she did that.” Presidents would have many such personal moments in subsequent decades.

A final context influencing the presidency is pluralism. America has grown dramatically more diverse over the past several decades, both in terms of sheer demographics and in the extent to which issues of inclusion and equity circulate in public discussion. For presidents, these shifts provide two very different rhetorical possibilities. One approach is to embrace the nation’s changing contours, speaking more with and about minority communities. This was the approach Clinton, George W. Bush, and Obama took. For instance, each of these presidents gave more interviews than had their predecessors to media organizations that primarily reached minority communities, and they also talked much more about diversity than had been common in the presidency to that point. Trump took quite a different approach, leveraging pluralism to stoke fear and play upon prejudices. In one prominent example, Trump tweeted that four members of Congress collectively known as “The Squad”—Alexandria Ocasio- Cortez, Ilhan Omar, Ayanna Pressley, and Rashida Tlaib—should “go back” to “the totally broken and crime infested places from which they came.” Apart from having his facts wrong (all except Omar were born in the U.S.), it was impossible to ignore that Trump had specifically called out four women of color, including the first two Muslim women ever elected to Congress. Trump’s language was a far cry from the last Republican president, George W. Bush, who routinely talked about how Muslims, like people of any other faith or no faith at all, were “equally American.”

Change is inevitable in an institution as complex as the presidency. As the Biden

administration approaches the end of its first year, it is already clear that it represents

a departure from numerous aspects of the Trump administration. But amid those differences,

one thing remains constant: Biden, like all his recent predecessors, will need to

respond to the contexts that define the ubiquitous presidency.

Change is inevitable in an institution as complex as the presidency. As the Biden

administration approaches the end of its first year, it is already clear that it represents

a departure from numerous aspects of the Trump administration. But amid those differences,

one thing remains constant: Biden, like all his recent predecessors, will need to

respond to the contexts that define the ubiquitous presidency.

◀ The Ubiquitous Presidency, by Joshua M. Scacco and Kevin Coe, examines the intricate relationship between the president, news media, and the public.