Our National Vocabulary

was Tested

Johanna Watzinger-Tharp

ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS

On the Media host Bob Garfield uttered this statement during a segment that referenced the protests that erupted in summer 2020 around the U.S. in response to the murder of George Floyd. Divergent depictions of the events reflect fierce disagreements about their nature: Did we witness riots or peaceful protests against racial injustice? Did we see cities under siege or isolated violence? Was systemic racism of law enforcement at the root of George Floyd’s death, or was it inflicted by a bad apple?

As a linguist, I could not help but notice Garfield’s choice of the passive voice—our national vocabulary was tested. Using the passive voice shifts the focus to the recipient of an action, sometimes because the actor is not known or because we prefer for them to remain unnamed. The statement prompted me, as a listener, to reflect further on the role that language played over the course of last year. What or who tested our language? What does language we hear tell us about events we see? And does language provide clues that suggest how we experienced and coped with them?

COVID-19, racial unrest, and an insurrection attempt. Social distancing. Black Lives Matter.

Stop the Steal. Language acquires its meaning in context, in a specific situation, with speakers and listeners, or interlocutors, and their intents and purposes. Recent events have indeed tried and stretched the language available to us, but they have actually tested us and how we, as language users, choose to employ language—in ways that are beneficial or in ways that are harmful and hurtful.

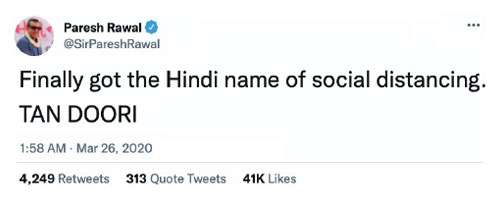

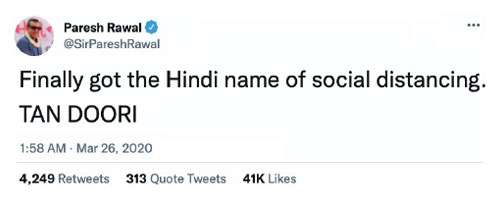

Social distancing became a key phrase to refer to the simple but effective strategy of staying home and apart during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, versions of this pandemic watchword turned up around the world: Soziale Distanz (German), distanziamento sociale (Italian); sotsial’noye distantsirovaniye (Russian); socialt avstånd (Swedish); and, coined on Twitter, tan doori (“tan” “body” and “doori” distance), employing humor to cope with coronavirus stress.

In spite of its inherent incongruity (how can we be social AND distant at the same time?), social distancing became an effective linguistic tool to help make the transition from our usual, closeproximity social selves to being safely apart (and finding ways to socialize, too). Put differently, when the coronavirus tested us, we employed language intentionally and beneficially to communicate what was needed to stem its spread. The meaning of social distancing is thus inexorably tied to the COVID-19 pandemic. And to many, this phrase also signifies societal inequities between those who had the privilege of staying home (and keeping their homes and their incomes) and those who were unable to stay home or faced financial ruin if they did.

We can think of Black lives matter as a speech act that demands a national reckoning with systemic racism and institutionalized violence

against black women and men. A societal transformation that replaces acceptance of killings as a regular occurrence to accountability of law enforcement. When the phrase Black Lives Matter was seen and heard during protests around the U.S. and in many places around the world, it was the context of George Floyd’s death, and of so many others, that made it meaningful. Our shared understanding of the premise and context of utterances are essential to successful communication. When people engage in conversations with others—in good faith—they intuitively abide by what linguists define as the cooperative principle; in fact, contextual factors and presuppositions routinely figure into a conversation without being explicitly stated.

Don’t all lives matter, some asked? Of course, they do, and that is precisely why this retort violates the cooperative principle. Black lives matter does not reply to a question about all lives and whether they matter or not. Rather, the question that we must confront is whether Black lives do actually matter in America, given the apparent disregard for Black lives and the persistent violence against Black men and women. As a blog by a group of linguists at Stanford University noted, “‘All lives matter’ is a hurtful, dismissive, and cruel response to ‘Black lives matter.’” While perhaps not intentionally cruel, the response “All lives matter” intentionally disregards a self-evident shared premise; it is uttered in bad faith. By suggesting that “Black lives” means only Black lives, those who use, or rather abuse this expression, cause harm.

How a hitherto shared premise can be replaced with a lie is plainly evident in the phrase Stop the Steal. Stop the Steal assailed a fundamental and shared assumption about the peaceful transition of power after an election. Not only is it an example of destructive language,

but it directly translated into destructive action, into the January 6 insurrection attempt that cost lives. It was all the more heartening, then, that the political transition from one administration to another on January 20 featured the restorative power of language. Amanda Gorman delivered a stirring poem, with this stanza that conveyed confidence and hope:

So while once we asked, how could we possibly prevail over catastrophe?

Now we assert,

How could catastrophe possibly prevail over us?

Catastrophe has tested our language and it continues to test us. Will we pass this test with a renewed sensitivity to language that will guide us toward using the power of language responsibly? Perhaps. But first we must reject language that instills pain and perpetuates racism and embrace language that fosters compassion and social justice.

|

Our National Vocabulary was Tested Johanna Watzinger-Tharp ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS |

On the Media host Bob Garfield uttered this statement during a segment that referenced the protests that erupted in summer 2020 around the U.S. in response to the murder of George Floyd. Divergent depictions of the events reflect fierce disagreements about their nature: Did we witness riots or peaceful protests against racial injustice? Did we see cities under siege or isolated violence? Was systemic racism of law enforcement at the root of George Floyd’s death, or was it inflicted by a bad apple?

As a linguist, I could not help but notice Garfield’s choice of the passive voice—our national vocabulary was tested. Using the passive voice shifts the focus to the recipient of an action, sometimes because the actor is not known or because we prefer for them to remain unnamed. The statement prompted me, as a listener, to reflect further on the role that language played over the course of last year. What or who tested our language? What does language we hear tell us about events we see? And does language provide clues that suggest how we experienced and coped with them?

COVID-19, racial unrest, and an insurrection attempt. Social distancing. Black Lives Matter. Stop the Steal. Language acquires its meaning in context, in a specific situation, with speakers and listeners, or interlocutors, and their intents and purposes. Recent events have indeed tried and stretched the language available to us, but they have actually tested us and how we, as language users, choose to employ language—in ways that are beneficial or in ways that are harmful and hurtful.

Social distancing became a key phrase to refer to the simple but effective strategy of staying home and apart during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, versions of this pandemic watchword turned up around the world: Soziale Distanz (German), distanziamento sociale (Italian); sotsial’noye distantsirovaniye (Russian); socialt avstånd (Swedish); and, coined on Twitter, tan doori (“tan” “body” and “doori” distance), employing humor to cope with coronavirus stress.

In spite of its inherent incongruity (how can we be social AND distant at the same time?), social distancing became an effective linguistic tool to help make the transition from our usual, closeproximity social selves to being safely apart (and finding ways to socialize, too). Put differently, when the coronavirus tested us, we employed language intentionally and beneficially to communicate what was needed to stem its spread. The meaning of social distancing is thus inexorably tied to the COVID-19 pandemic. And to many, this phrase also signifies societal inequities between those who had the privilege of staying home (and keeping their homes and their incomes) and those who were unable to stay home or faced financial ruin if they did.

We can think of Black lives matter as a speech act that demands a national reckoning with systemic racism and institutionalized violence against black women and men. A societal transformation that replaces acceptance of killings as a regular occurrence to accountability of law enforcement. When the phrase Black Lives Matter was seen and heard during protests around the U.S. and in many places around the world, it was the context of George Floyd’s death, and of so many others, that made it meaningful. Our shared understanding of the premise and context of utterances are essential to successful communication. When people engage in conversations with others—in good faith—they intuitively abide by what linguists define as the cooperative principle; in fact, contextual factors and presuppositions routinely figure into a conversation without being explicitly stated.

Don’t all lives matter, some asked? Of course, they do, and that is precisely why this retort violates the cooperative principle. Black lives matter does not reply to a question about all lives and whether they matter or not. Rather, the question that we must confront is whether Black lives do actually matter in America, given the apparent disregard for Black lives and the persistent violence against Black men and women. As a blog by a group of linguists at Stanford University noted, “‘All lives matter’ is a hurtful, dismissive, and cruel response to ‘Black lives matter.’” While perhaps not intentionally cruel, the response “All lives matter” intentionally disregards a self-evident shared premise; it is uttered in bad faith. By suggesting that “Black lives” means only Black lives, those who use, or rather abuse this expression, cause harm.

How a hitherto shared premise can be replaced with a lie is plainly evident in the phrase Stop the Steal. Stop the Steal assailed a fundamental and shared assumption about the peaceful transition of power after an election. Not only is it an example of destructive language, but it directly translated into destructive action, into the January 6 insurrection attempt that cost lives. It was all the more heartening, then, that the political transition from one administration to another on January 20 featured the restorative power of language. Amanda Gorman delivered a stirring poem, with this stanza that conveyed confidence and hope:

So while once we asked, how could we possibly prevail over catastrophe?

Now we assert,

How could catastrophe possibly prevail over us?

Catastrophe has tested our language and it continues to test us. Will we pass this test with a renewed sensitivity to language that will guide us toward using the power of language responsibly? Perhaps. But first we must reject language that instills pain and perpetuates racism and embrace language that fosters compassion and social justice.