Recovering Identities of Black Latter-Day Saints

In a letter read to her congregation in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1982, Freda Lucretia Magee Beaulieu described July 21, 1978, as the happiest day of her life. This day came after she traveled nearly 1,000 miles from her home in New Orleans, to the church’s temple in Washington, D.C. to be sealed by proxy to her husband who had passed away six years earlier.

Baptized in 1909, it wasn’t until 69 years and 23 days later that Beaulieu, who was black, was allowed to enter a church temple to be sealed for eternity to her husband. A faithful member of the church since the age of 9, the happiest day of her life was one she feared may never come. Regardless, she remained devoted to the faith following the foundation set by her parents.

She recalled her childhood as happy and filled with fun times, especially when the family would surround the piano, sing and enjoy each other’s company. She learned to read the scriptures, pray, observe the World of Wisdom (the church’s health code), and make her charitable contributions.

“We always had prayer morning and night and scripture study before going to bed,” said Beaulieu in 1982. “Once in a while missionaries would come by and spend some time teaching us more about the gospel.”

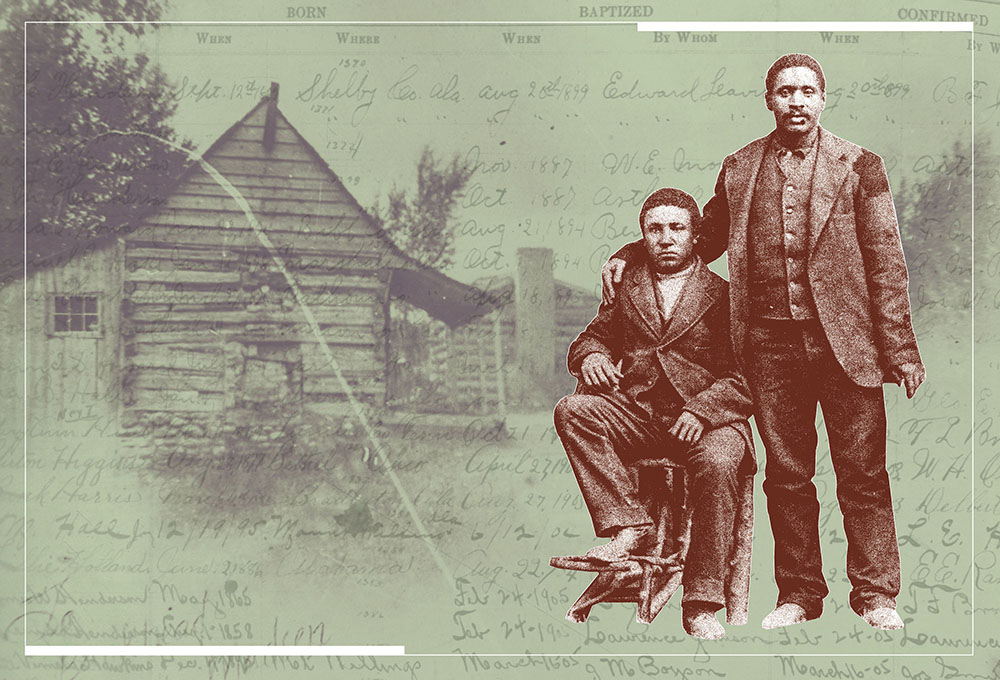

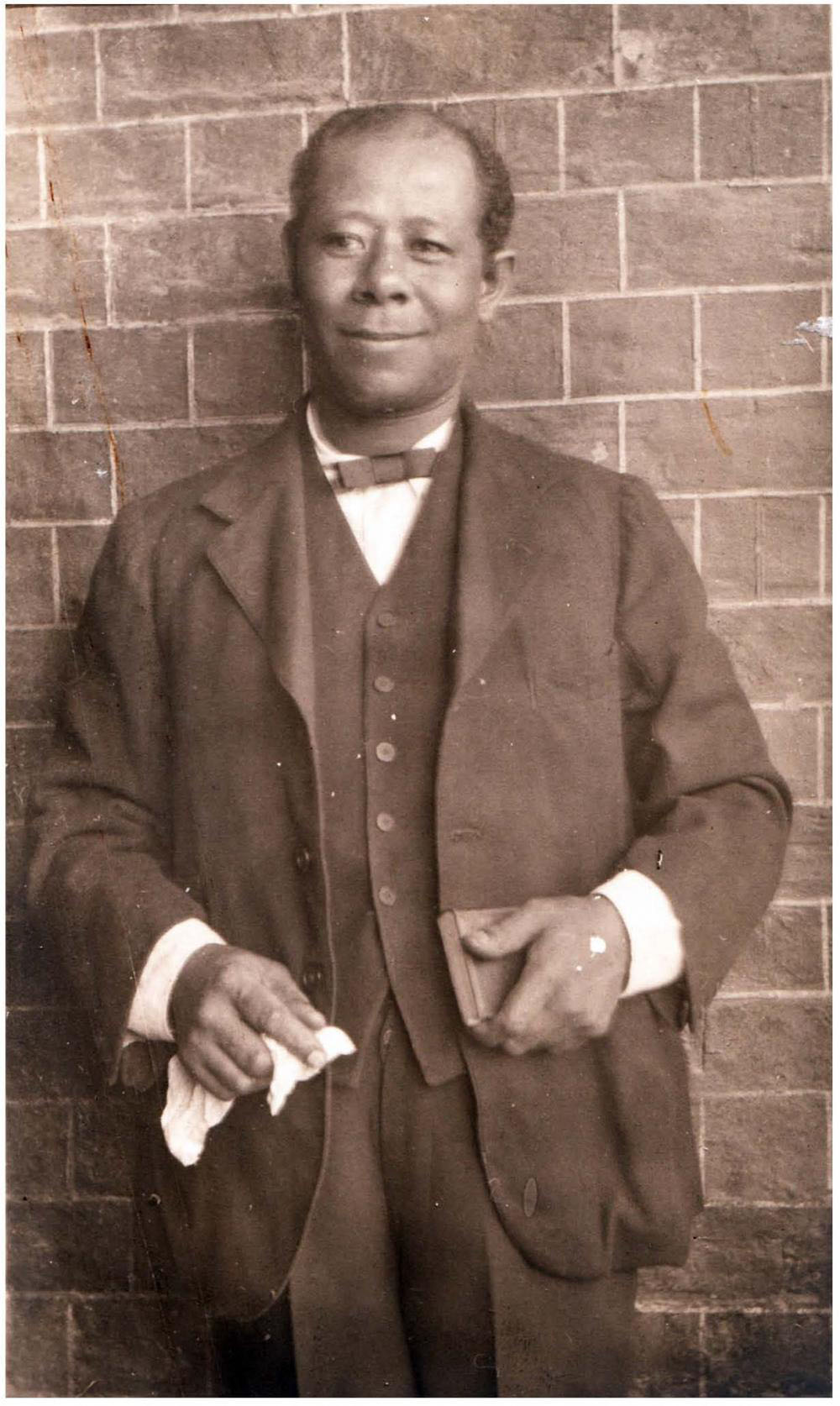

Stories like Beaulieu’s can be found in Century of Black Mormons, a digital history database, documenting and recovering identities and voices of black Latter-day Saints during the faith’s first 100 years (1830-1930). It contains digitized versions of original documents, photographs, a map documenting baptismal locations, a timeline, and biographical essays telling the stories of black Latter-day Saints. The archive currently contains almost 70 biographies and over 200 more will be added before the project is completed.

Paul Reeve, Simmons Chair of Mormon Studies in the University of Utah’s Department of History, created the project, in partnership with the J. Willard Marriott Library, as a way to counter the public perception that there aren’t any black members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. To date, no scholar has attempted to identify black Latter-day Saint pioneers of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

“The first black member was baptized in 1830, the founding year of Mormonism,” said Reeve. “Rather than write a book, I wanted to engage the public in a different way. The database makes the actual sources which document the lives of black Latter-day Saints available to the public. It brings together in one location names, dates, census records, LDS membership records, and other sources and makes them publicly available for the first time. The evidence speaks for itself.”

Creating a Generous Interface

Recognizing the need to develop a database that is accessible and simple to navigate, Reeve participated in a digital history institute at George Mason University funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities. There, he learned how to create a “generous interface” that is designed to allow users to explore the database on their own terms by presenting the information in a variety of ways.

“There is no one set way to enter a database,” said Reeve. “If you try to control the data for a user who may not know what’s available, they might miss all kinds of things. The philosophy I learned at the institute is that you allow users to find the data for themselves.”

With this philosophy in mind, Reeve enlisted the help of the Marriott Library and the Digital Matters Lab to move forward with what he had learned. With the expertise of Anna Neatrour, digital initiatives librarian at the Marriott Library, and using Omeka S software, Reeve and his team created a database using different platforms such as maps and timelines to present the data and allow users to explore in a way that works best for them.

“There was a lot of pieces the site needed to display and it was fairly complex,” said Neatrour. “Paul had a clear vision of what he wanted and I helped translate that into what was possible on the website. Century of Black Mormons is the most complex digital exhibit I’ve worked on.”

Centered on biographies, the data is categorized around the four themes of who, when, where, and how many. In presenting the information in these various visual ways, Reeve was surprised to find patterns he hadn’t recognized before, specifically the geographic spread of baptisms.

“The church is an American born faith, so we were surprised by the international component of conversion of people of black African descent. There were early missions to South Africa in 1853, but we weren’t aware of any other international converts. We have found one in London in the 1850s, three who were baptized on the Atlantic Ocean in 1853, and three in South Africa, and we believe we will identify more.”

The map unveiled another surprising detail that Reeve hadn’t noticed before—the pattern of baptisms across the United States.

“Baptisms shape sort of a crescent from the upper Midwest, Northeast, down the Atlantic coast, and all across the South. The interesting phenomena is the dearth in the American West, except for an unexpected number of baptisms in Utah. Second-, third-, fourth-, and fifth-generation Mormons represent a growing number of Utah-based baptisms and, so far, account for all of the baptisms between 1873 and 1891. Of the 20 Utah baptisms thus far, 65% were of people who were second-generation, or later, Mormons. As Mormonism reinvigorated its missionary program by the 1890s in the wake of a federal anti-polygamy crackdown, baptisms outside of Utah followed through the 1930s.”

Research

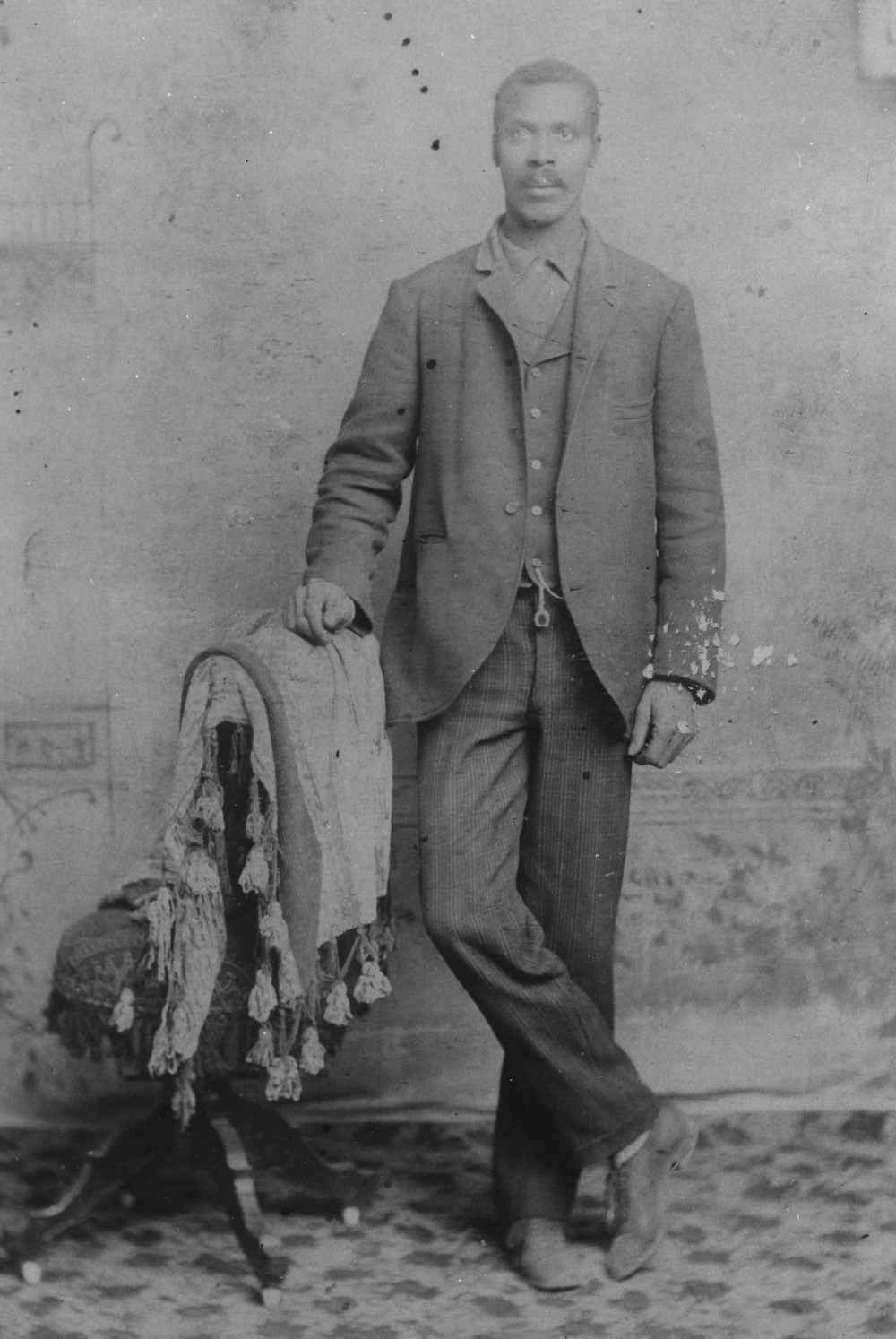

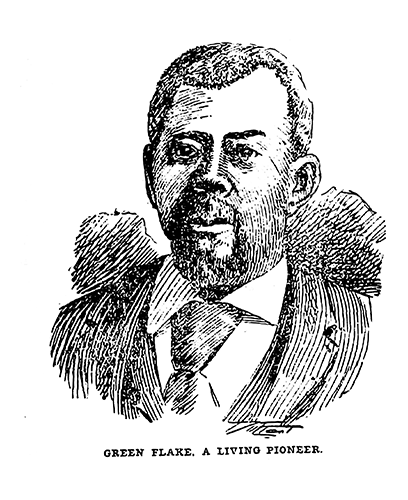

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints doesn’t track membership by race making it difficult to identify the earliest black members. To begin the project, Reeve created a list of names he already knew along with their descendants and added the names of well-known black pioneering Latter-day Saints such as Elijah Abel and Jane Manning James. From there, he began to dig.

A few examples from the database include:

- Elijah Banks was born in Tennessee in 1855 to a father he could only identify as “a

colored slave.” He converted in Minneapolis in 1899 and taught Sunday school.

- Julia Miller Lamb was a former slave who bore 14 children and was married for more

than 60 years. She was baptized in 1898 in Union, North Carolina, when she was in

her mid-70s.

- Paul Thomas Harris was a convert from Johannesburg who loved to feed the missionaries.

- Daniel Bankhead Freeman was baptized in 1865, in South Cottonwood, Utah, around the age of 11. He was identified in his baptismal record only as “Daniel of the colored race.” He died in Corinne, Utah, after being kicked by a horse.

He searched through microfilm at the Church History Library, he enlisted the help of fellow scholars, he shuffled through papers and photos trying to find any shred of information. Surprisingly, his biggest breakthrough came from the prejudice of the time.

“Even though there is no official column for race in the church’s membership records, the clerks would sometimes scrawl ‘colored’ next to a black convert’s name. It illustrates the way in which white was deemed normal and a variation from white was considered noteworthy.”

One discovery occurred as Reeve was scrolling through microfilm baptismal records looking for a particular name and he just happened to notice the word “colored” scribbled in the margin, which led to the discovery of the entire Magee family who were baptized in 1908 and 1909 in Southern Mississippi. Freda Lucretia Magee Beaulieu was one of 11 members of her family eventually baptized.

Other clues have come from the diaries of missionaries, in which they would write about the baptisms of black members but wouldn’t include names.

“We have six names to add to the database from 1869 that came from a missionary diary. In the diary, the missionary lists the first and last names of four white people he baptized and then simply writes that he baptized six black people but did not list their names or any other details.”

Through his research, Reeve has found many clues of early black members, but getting official information isn’t easy. In a notebook from Wilford Woodruff, an early church leader, he found the names of five converts in Tennessee from 1835 but has located few additional traces of evidence to document their lives.

“Even if we have a name, finding out additional biographical information is enormously difficult because these are people who left no written record behind. All five were enslaved, had no rights, and they only show up in census records as the property of someone else. They don’t have birth or death certificates and were it not for Woodruff’s notebook they may have been lost to history.”

Networking has been an effective way to add biographies to the database. Reeve has received emails and phone calls from the public who want the names of their family members represented on the website. With the names and some basic information in-hand, Reeve and his colleagues can begin to do research and find information of which the family may not be aware.

After reading an article in The Salt Lake Tribune about the project, Deena Porcaro Hill contacted Reeve about adding her third great-grandfather, Nelson Holder Ritchie, to the database. A few years ago, Hill began looking into the history of Ritchie, whom she believed was of Cherokee descent. She and other family members had their DNA tested and found they had African American heritage, which came as a complete surprise.

“We were all blown away,” said Hill. “Armed with this new information, I began contacting all the African American DNA matches to all our family members and a pattern started to form and after several hundred hours of research, emails, phone calls, and a trip to North Carolina to meet with our new cousins, I discovered that Nelson was a slave and so was his mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother.”

Through DNA testing, Hill was finally able to find out about Ritchie’s parents, her own African American heritage, and connect with new family members. She gathered documents and data and was eager to have Ritchie remembered in the Century of Black Mormons database.

“I am beyond excited about Paul's database. He has ensured that this group of faithful

saints have not been forgotten and will never again be forgotten. I will always be

eternally grateful to Paul and his dedication to this project,” said Hill.

[This database] has ensured that this group of faithful saints have not been forgotten

and will never again be forgotten.

Even through networking, investigating, and tedious research, it’s not possible to get an accurate number of black members who were baptized in the first 100 years of the church. Pre-Civil War records are sparse and census records did not list the names of enslaved African Americans. As a result, former enslaved people do not show up on census records by name until 1870 and church records only listed race when an individual felt compelled to write it down.

“Whatever number we end up with for the first 100 years it will be an automatic underrepresentation because clerks or missionaries did not always write ‘colored’ next to a black convert’s name. Even still, we suspect that by the time the research is complete we will have somewhere between 300-400 individuals in the database.

For now, Reeve and his team will continue to search, dig, and verify any bit of information they can. Individuals who have names, documents, photographs, or other supporting evidence of black Latter-Day Saints, can email centuryofblckmormons@gmail.com. To explore Century of Black Mormons, please visit , https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/welcome.