Intersectionality Here and Now: Three Years Later

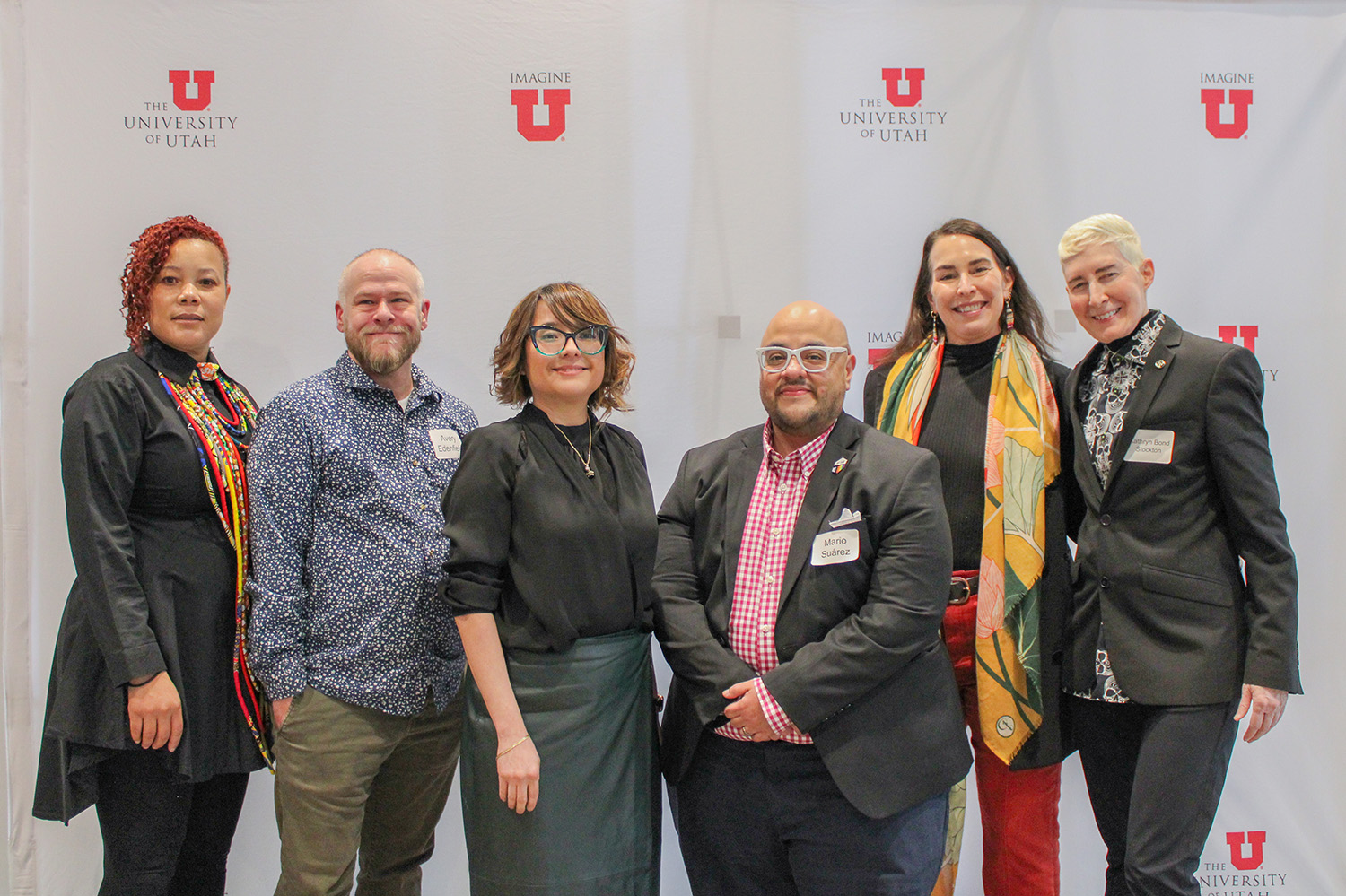

From left to right: Andrea Baldwin, Avery Edenfield, Annie Fukushima, Mario Suárez, Wanda Pillow, and Kathryn Bond Stockton.

In early January, the School for Cultural & Social Transformation and the College of Humanities hosted a panel discussion on intersectionality, bookending a three-year Transformative Intersectional Collective (TRIC) grant from the Mellon Foundation. The panel brought together distinguished scholars to discuss the state of intersectional work in Utah, reflect on successes and challenges, and look to the future. The event, funded through the Mellon Foundation grant, provided a vibrant forum for heartfelt intellectual conversation, rekindling old partnerships and forming new connections.

Though it was brisk and chilly outside, the mood among the 130+ attendees gathered in the softly lit University of Utah Alumni House was warm and collegial. Powerful quotes from key intersectional texts and a video from the Black Feminist Eco Lab’s recent Celebration of Life event played on a loop in the background serving as both a prelude to the afternoon’s discussion and an exemplar of intersectional work in Utah. The crowd filtered in, exchanged greetings, and tossed coats over seat backs, the hum of anticipation falling to a hush as the event began.

“This is a joyful moment – we’re not going to be naïve with our joy – we never are, but if we do not feel our joy and gather our collective power, we will be defeated.”

Wanda Pillow, Acting Dean of the College of Humanities, introduced the event. Her remarks took the audience on a brief explanatory tour of the academic and cultural history of intersectionality since its initial formulation by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw in the 1989 paper “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex.” With nods to the work of the 1979 Combahee River Collective, Yomaira Figueroa, Jacqui M. Alexander, and Audre Lorde, Pillow directly acknowledged the apprehension that many in the higher education community are feeling at this moment: “As our team reflected on the last three years in preparation for the event, we discussed how much the political and policy context has changed in Utah and nationally. I know the panelists will speak to this and discuss current challenges, but here I will share that when planning this event I was repeatedly asked, ‘Are you sure you can talk about intersectionality?’ I am here to say: yes we can, yes we are, and yes we will.”

Pillow noted that intersectionality is often used as a placeholder term, stripped of its meaning, and that although “intersectionality wars” erupt into viral snippets in our modern political and media landscapes, the term itself is simply an accurate way to describe the lived experiences of many people. She reminded the audience that actively building community is key to intersectional praxis, relying on an ethos of “When I can, and as I am able, I will carry more,” so our exhausted colleagues, family, friends, and neighbors who are bearing a heavy load can have a rest in turn.

The panel, moderated by Kathryn Bond Stockton, Distinguished Professor of English and inaugural dean of the School for Cultural & Social Transformation from the University of Utah, featured prominent scholars including the U’s Annie Isabel Fukushima (associate professor of Ethnic Studies), Andrea Baldwin (associate professor of Gender Studies), as well as colleagues from Utah State University – Mario Suárez (associate professor of Teacher Education and Leadership) and Avery Edenfield (associate professor of English).

Stockton opened the discussion with a call to exuberance: “This is a joyful moment – we’re not going to be naïve with our joy – we never are, but if we do not feel our joy and gather our collective power, we will be defeated.” Launching from that, the panelists’ conversation explored several key themes: the nature and impact of intersectionality; tangible outcomes from the grant's implementation; current challenges in conducting intersectional work in the world today; and future directions for advancing intersectional work in our individual and collective lives.

On the nature of intersectionality

Each panelist shared a personal conceptualization of intersectionality, starting with Baldwin, who addressed it “through the lens of a long arc of global Black feminism…our humanity, our legibility, our visibility. It means to stand up for Black women every day. I’m paraphrasing here, but if Black women are free, then everybody will be free. As I do this work, then other people will also benefit.”

Suárez reflected on his childhood growing up on the Texas/Mexico border and his early career in teaching high school mathematics. He conceptualizes intersectionality as “all these different parts of my identity – moving back and forth and shapeshifting, navigating different worlds – that I cannot separate.”

Fukushima exhorted the audience to remember that intersectionality is more than “an analytical tool, a framework, a methodology; not a grand theory but a praxis.” She also connected intersectionality with concepts of genealogy in terms of who we are thinking with and intellectually engaging as well as the everyday ways we engage with our communities.

Edenfield delved into an intersectionality that requires us to take responsibility for our complicity as part of institutions and in our own communities, and the need to “go back and own my mistakes, publishing about those mistakes, and talking about how we can do better.”

“During COVID, I took up gardening, and I’ve had to learn a lot. One thing I learned was about mint. It has deep, deep root systems. You can cut all the above-ground things off, but it will still keep growing. We need to collectively put down deep roots that will keep growing.”

On community

Panelists explored the complex realities of implementing intersectional approaches in Utah, including the joys of cross-institutional collaboration with colleges and universities across the state. Suárez credits the TRIC grant with helping him to build community in Utah; having moved from Austin to Logan right before the pandemic to join the faculty of Utah State University, it was a struggle at first. “I don’t think I would have stayed in Utah had it not been for [the] TRIC and the community that we have been a part of through this at USU,” said Suárez. “We have met and made friends and formed lifelong friendships that we wouldn’t have made without it…there’s not that many individuals who are doing this kind of work, so it's been really great to have this community that has helped me to love it [Utah].”

Likewise, Fukushima listed numerous successful initiatives that stemmed from the community created through the TRIC grant and called the audience into the space of intersectional work as colleagues and collaborators. Projects spanned a range of topics from the transcontinental railroad to the Utah Prison Education Project to gender-based violence and reached far across the state.

On facing the challenges before us

In answer to a question about how to move forward given the challenges that we are facing, Edenfield shared his practice of facing the challenge by grounding himself in his personal mission to make institutions less harmful. “The university itself is not a safe space, and I have to accept that. It’s not naturally a caring space. But the people who work there can be caring, and can create safe spaces. There are people who have courage, who are grounding their work in love and care, and that’s where those pockets of intersectional work are going to happen.”

Baldwin brought up the sobering challenge of balancing the work with the safety of her family, and choosing to say no to some things that would create too much of a security risk. “I’m not going to be silent, but how do I do this work, stay safe, keep my family safe, and stay mentally healthy? My pivot would be to reimagine what comes after intersectionality,” she said. “Sometimes we put the work that came before us on a pedestal. While intersectionality is important, we may have to let it go a little bit in order to change and grow and be visionaries about what we do next.”

Suárez advocated for a praxis of creative insubordination, a term coined by Dr. Rochelle Gutierrez, sharing an anecdote from the garden. “During COVID, I took up gardening, and I’ve had to learn a lot. One thing I learned was about mint. It has deep, deep root systems. You can cut all the above-ground things off, but it will still keep growing. We need to collectively put down deep roots that will keep growing.”

“This work is for the long haul. Some of this takes a long time. Our words are always changing and shifting, but so too can we."

Fukushima reminded the audience that “This work is for the long haul. Some of this takes a long time. Our words are always changing and shifting, but so too can we. Always take risks and be creative, enter spaces where you may not feel comfortable. Be comfortable with the uncomfortable!”

Stockton closed the panel’s invigorating discussion with an invitation, like Baldwin, to pivot – “from anger, to kindness, to structural change. It’s a recursive loop,” they said. “Anger is righteous; kindness is a surprise.”

A spirited question and answer session followed the panel discussion. Audience members posed engaging questions, from “What does solidarity look like in the framework of intersectionality?” to a thought-provoking, “What are the ideas that we need to let die, in order for us to move forward in this work?”

The event represented a culmination of the TRIC grant's work in building relationships between scholars doing intersectional work within Utah and in concert with five other universities in the country. It aimed to provide a space for academic and community members to connect, reflect, and discuss strategies for moving forward in challenging times. In the reception following the event, attendees mingled with one another and panelists, exchanging ideas, commiserating about concerns, and bolstering one another with hopes and support for intersectional work moving forward.

Crystal Rudds, assistant professor of English at the University of Utah who attended the event, expressed appreciation. “This panel was a great reminder of the rigor of intersectionality as an intellectual tradition but also its deep humanity,” she said. “And humanity is what we’re hungering for in these times."

Ultimately, while the event was very direct in acknowledging the realities of the situation and the challenges involved in intersectional work, it seemed to tap a wellspring of energy and a determination in the ways that Utah’s intellectual and activist communities are moving forward – arms linked, sharing the load.