Isabel Dulfano, Professor in the Department of World Languages and Cultures, visits the Archives in San Cristobal de las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico.

San Cristobal da las Casa, Chiapas, Mexico archival building.

Archival work can take so many forms, particularly as one encounters the challenges of travel to foreign lands. From hard-to-find archives with inadequate signage, to local violence, research in the archives in San Cristobal de las Casas turned out to be a mixed experience. For example, on the day I arrived at the archives I learned that fourteen people had died nearby the day before, likely the victims of drug cartel activity.

My project in the archives was to research Indigenous women’s writing. To this end I wanted to visit two locations, the Diocesan Historical Archive of San Cristobal de las Casas (AHDSC), and the printing press run by artist printers from Taller Leñateros in San Cristobal de las Casas.

The Chiapas region is an area densely populated by Indigenous pueblos (Tzeltal, Tzotzil, Chol, Tojolabal, Chuj, Kanjobal, Jacalteco, Chontal, Mam, Lacandon among others). The Diocesan Historical Archive houses a wide spectrum of colonial documents that survived through the Mexican Revolution and Carrancista invasion of the region, together with the Catholic Church’s proprietary collection. One might imagine that access to relevant documents might not be too difficult given modern technology and a digitized system of cataloguing documents - indeed, I had already made careful preparations prior to travel to view the documents as well as in situ online resources. However, the diocesan archive proved challenging to use.

The first hurdle was finding the actual location of the Diocesan Historical Archive. It turned out to be ensconced in a tower, up an external stairway behind the Cathedral of San Cristobal, next to a chapel in a rear courtyard, and with no signage. Once I was finally able to verify its location, I entered. The room was musty, filled with black folder boxes on floor-to-ceiling shelves, portraits of the archbishops, including the first of Bartolome de las Casas, and a stylized classic wooden ambo stationed in the middle of the library space.

I approached the archivist who was unable initially to help me narrow my focus or assist in honing my search, but who eventually steered me toward the general catalog categories. The catalog offered no gender-specific category, so access to the Indigenous women’s documents had to be gained by looking through entries for ‘witchcraft,’ ‘census,’ ‘matrimony and sexuality’ (infidelity and divorce). These entries revealed reports written in 1619, in a script that was at times indecipherable, on variously named “the Indian” subjects.

This photo is a view of the archival reading room, though researchers can only work in the small space in front of the poster seen closest to viewer.

These summarized the documented court cases. Notable was the formulaic nature of the testimonial narrative structure, in which the judge literally traced the case as told by the plaintiff, defendant’s response, witnesses and ultimate sentence as handed down by said author. Each section was clearly marked in the margins together with other scribbles, indicating the role of the speaker. The markings referencing the witness testimony and other parts of the narrative were uniform throughout the transcription, written in longhand. The documents centered on general topic of witchcraft provided the most extensive information on Indigenous women of the period, although very few were available or in good condition. Consequently, like searching for a needle in a hay stack, the process of finding useful 16th and 17th century documents proved tedious and at times off-putting. On the other hand, the content and judge’s narrative summary opened a window into life during that period, with minutiae to entice the curious. I intend to follow-up in other parts of Mexico to gain a broader perspective on the topic.

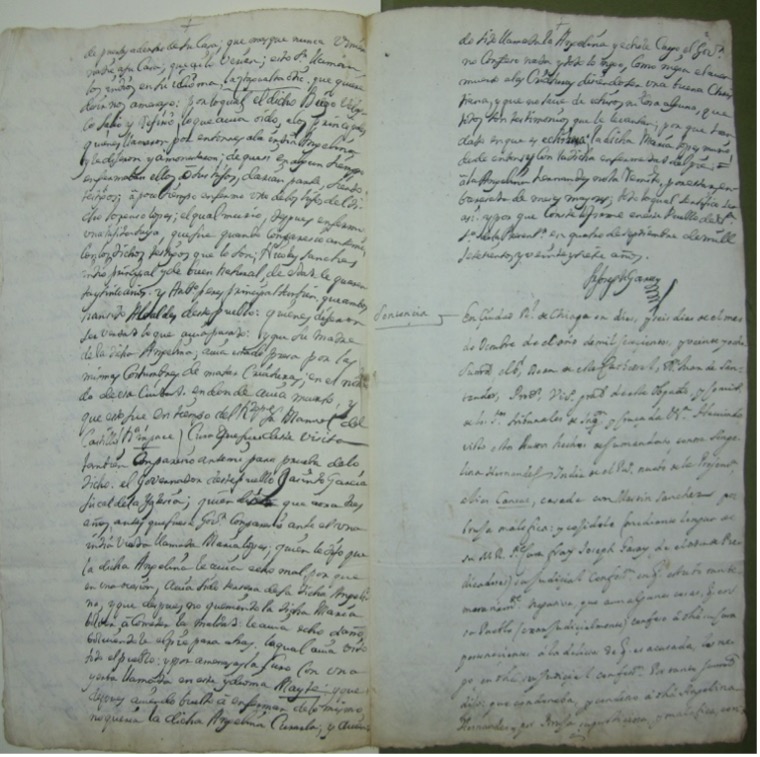

The picture is an excerpt of the signed preface and detail of the "denuncia" (written in left margin)/charge filed against the Indigenous woman.

By contrast, the visit to the Taller Leñateros, a contemporary Indigenous women’s printing press of artist books, several examples of which are held at the Marriott Library Rare Books Special Collection, was completely inviting. The press is a women’s collective, started in 1975, that produces its own paper and sustainable books in collaboration with Maya women authors.

Finding the press was straightforward. Upon entering, I was met by women fabricating the books and envelopes sold in their store. I was welcomed on a tour to view the production sites in the rear. Using recycled materials and natural fibers from plants, the artisan showed me how she prepares the paper in a large tin basin and allowed for photos of each step of the process. Her gloved hands mixed materials (ink, water, palm and bougainvillea leaves and/or other natural fibers) in a metal vat of black pulp and then strained the mixture onto a silk screen, flipped it onto a metal plate, and set out into the sun to dry. The second room housed the letter press and reams of colored paper, another 20th century screen press and an intaglio printer for inscribing text onto the page. Moving into the front courtyard, women and teenage girls assembled the book, in this case, with red felt handsewn hearts, glued pages, and cardboard handmade envelopes. The courtyards brimmed with old books that provide the recyclable paper, hanging plants and flowers drying from available rafters, walls covered with intaglio prints from books and artists associated with

Woman with ink staining tin.

the press and plants. To view their artists’ books, visit Marriot Library Rare Books Collection. However, just as a visit to the Rare Books provides the researcher a thrilling hands-on experience with assorted 16th century texts, travel to an archive makes real the functioning of legal adjudication during a specific period with a plethora of documents to peruse. It offers an unparalleled experience with original texts in their home setting.

The case discussed was heard in a Chiapas court, where it remains to this day for our viewing with a bit of persistence. This trip contributed a piece in this research project on Indigenous women both in contemporary as well as early post-conquest Mexico, which will be presented at a conference this year.