"It gives me back my identity":

College of Humanities and the Utah Prison Education Project

Pamela Cappas-Toro stands to speak at the UPEP panel in the College of Humanities.

What does it mean to engage in the humanities in a dehumanizing environment?

The Utah Prison Education Project (UPEP) has been at the University of Utah since it was co-founded by Erin Castro, Associate Professor of Educational Leadership & Policy and Associate Dean of College Access and Community Engagement, and a group of undergraduate students in the 2016-2017 academic year. UPEP admitted its first cohort of degree-seeking students through the College of Humanities for the 2024-2025 academic year. Says Castro, “I am incredibly proud of the Education Justice team here at the U of U, our supportive colleagues across campus, and our courageous students. I am especially proud of our director, Dr. Andy Eisen, whose steadfast leadership (and patience!) made all of this come together.”

This fall, a panel of faculty from the U and BYU as well as a UPEP alumna, discussed the experience of teaching and learning in prison. Panelists included Leandra Hernandez, Assistant Professor of Communication; Lindsey Drager, Assistant Professor of English; Matt Mason, Professor of History at BYU; and Lia Olive, an undergraduate student in Communication and UPEP alum.

Olive considers her experience with UPEP to be the first time she engaged in rigorous, collaborative learning. “The instructor and all the T.A.’s were different than my other instructors [from other institutions]; UPEP staff and faculty seemed to care more about our learning than taking up seat hours,” she says. “At first, I thought that the curriculum they taught us was ‘dumbed down’ because we were incarcerated…I learned quickly that the level of rigor that instructors brought into the prison was no different than what was being taught in traditional classes.” This approach was transformative for Olive, who credits UPEP with helping her develop a genuine love for knowledge and a continuous desire to learn.

"It gives me back my identity. In prison you're known by your last name, your number, and your crime. In higher ed, I'm known by my name and what I bring to the classroom."

Panelists discussed what inspired them to become involved with the Utah Prison Education Project. Hernandez, Drager, and Mason reflected on how teaching at the prison has impacted their teaching in traditional campus settings, and Olive shared how participating in the program prepared her for transitioning to life after incarceration. “Coming to a traditional college campus is difficult for anyone, but after doing 18 ½ years in prison with only two years of in-prison college classes under my belt, I was terrified,” remembers Olive. “But UPEP helped me understand that I am a scholar, I can do this, and that’s all that matters.”

Audience members participated in an active Q&A session, asking about ways to become involved in the project, how UPEP has grown and changed over time, and how censorship impacts teaching within prison settings. “Erin [Castro] was my doctoral student,” shares Wanda Pillow, Acting Dean of the College of Humanities, smiling. “Ever since her dissertation, she has been committed to opening access for all students. It has been so amazing to see this program that she co-founded become such a nationally-recognized force for good, and I’m so thrilled that our college is playing a role in that development.”

“Although my freedom is limited, my mind and the ability to grow is not.”

Pamela Cappas-Toro, Operations Director for the forthcoming national center on prison education research and leadership and Adjunct Associate Professor of World Languages and Cultures, elaborates on the structure of the new comprehensive humanities degree. “It’s a BA in University Studies with a concentration in the humanities, so we wanted to make sure students could have an experience across different departments in the college. They take courses in history, philosophy, writing studies, linguistics – the full range of the humanities,” she explains. “It’s not only the degree they are getting, it’s also a certificate in Professional and Technical Writing with courses across different disciplines.”

UPEP students and instructors.

There are, to be sure, operational challenges to running such a project in the inherently restrictive setting of a prison. The bachelor’s degree program is rolling out slowly, offering first one, then two, and eventually three classes per semester in order to test out all the technology and give students a chance to get familiar with tools like Canvas. The environmental and security constraints mean that UPEP does not simply replicate the campus inside the prison classroom. Reflecting on her 15 years’ experience teaching in prisons in several states, Cappas-Toro says, “There’s a lot of possibility in what can happen inside, and a lot of creativity for instructors. You don’t have the same resources, you don’t have the same learners. You have a lot of adult learners with more lived experience, and that necessarily informs your teaching.”

Mike Middleton, Associate Dean of Academic Affairs at the College of Humanities, offers praise for the collaborative efforts to bring this degree program to fruition. “It is exciting to see this program continue to develop,” says Middleton. “UPEP does extraordinary work to make the program accessible and, over the last year, faculty from every department in the Humanities have collaborated to help design and support a curriculum that combines the critical, self-reflective thinking that is the trademark of the humanities with practical, skills-oriented courses to help further expand futures available to UPEP students.”

Cappas-Toro also reflects on how her experiences teaching in prison classrooms have changed her pedagogical philosophy on campus, offering an example of the ways that standard syllabi can often be very punitive to students, such as automatic grade reductions for missing more than two classes in a semester. In the prison setting, says Cappas-Toro, “If there’s a lockdown and I can’t get inside to teach, I don’t want to penalize students for that. If students are late in the prison, it’s usually because something happened outside their control. If they have to decide between a visit with a family member and your class, they’re going to choose their family member. The punitive training that we get when we’re in grad school – we start to unlearn that and apply that to our regular campus work.”

Leandra Hernandez, Assistant Professor of Communication, taught a summer session of Intercultural Communication through UPEP, and agrees about the impact that stretches outside of the classroom. “Teaching with UPEP at the Utah Correctional Facility was such a meaningful experience. Given that the course ran for only six weeks, we became acquainted and close very quickly,” Hernandez says. “I also appreciate how well UPEP works to keep faculty members connected with students after the course ends through end-of-term dinners at the correctional facility, which ensures continuity and meaningful faculty-student mentorship relationships.”

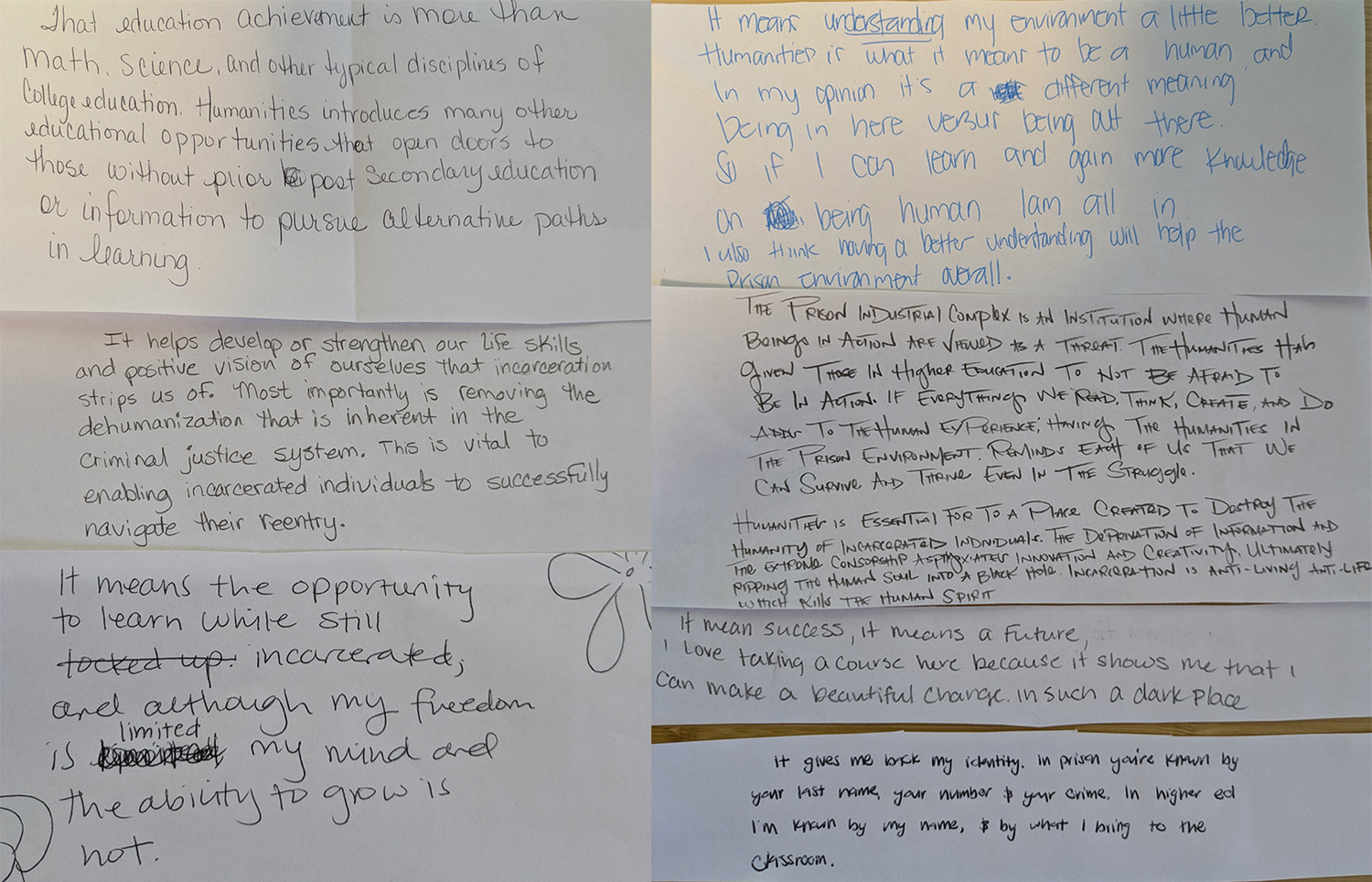

UPEP students' written answers to the question, What is it like to study the humanities in a dehumanizing environment?

Because of the nature of the program, interviews with current students are difficult to arrange. However, Cappas-Toro agreed to pose the question to her students: what is it like to study the humanities in a dehumanizing environment? Several students responded by sending handwritten notes, an implicit acknowledgement of the censorship and analog means with which they are permitted to work. Students wrote of how the humanities gave them hope for their own possible futures, of the inherent value and beauty of understanding the human condition, of the way engaging with the humanities restores a sense of self, of identity, of worth.

“If everything we read, think, create, and do adds to the human experience, having the humanities in the prison environment reminds each of us that we can survive and thrive even in the struggle,” writes one anonymous student. “Humanities are essential in a place created to destroy the humanity of incarcerated individuals.”

Compared to some of the technical training that is more commonly available in prison education programs, UPEP’s humanities degree gives students a highly sought-after opportunity for freedom of expression. Students engage in meaningful work, such as creating a One-Stop-Shop Student Center within the prison, where they will run humanities programming for their peers; co-curating an exhibit with the Utah Museum of Fine Arts that will be on display at the prison in March; helping select a Sundance film to screen in January with Q&A with the filmmakers, and advising on the development of a Venture Course with Utah Humanities (UH).

"It helps develop or strengthen our life skills and positive vision of ourselves that incarceration strips us of. Most importantly is removing the dehumanization that is inherent in the criminal justice system. This is vital to enabling incarcerated individuals to successfully navigate their reentry.”

Josh Wennergren, Director of the Center for Educational Access at UH, says of the students in the program, “The first time I walked into that classroom, I had assigned a reading to do a little bit of teaching and give them a preview of what a Venture course experience looked like. I was absolutely blown away by the preparedness and amount of engagement they brought to that discussion. It immediately showed me that there is such a hunger for this type of experience.”

The capstone project for the degree entails a year-long class where students engage in deep study about anything they truly care about through a humanistic lens. Cappas-Toro says this flexibility is one of the reasons UPEP partnered with the College of Humanities; even before UPEP offered a full degree program, students had a high interest in enrolling in humanities courses.

Students are enthusiastically tackling capstone projects about exercise and fitness programs, nonprofit management, entrepreneurship, and art, among others. It’s a stark contrast to much of their daily lives inside the prison, characterized by routines of control and obedience, being told what to do and not having much say on the process.

And perhaps that is an answer to the original question; in a dehumanizing environment, studying the humanities is a means to practice intellectual freedom and choice in a way that is poignantly unavailable – for now – through any other means.