Promise and Peril: Humanities Perspectives on Artificial Intelligence

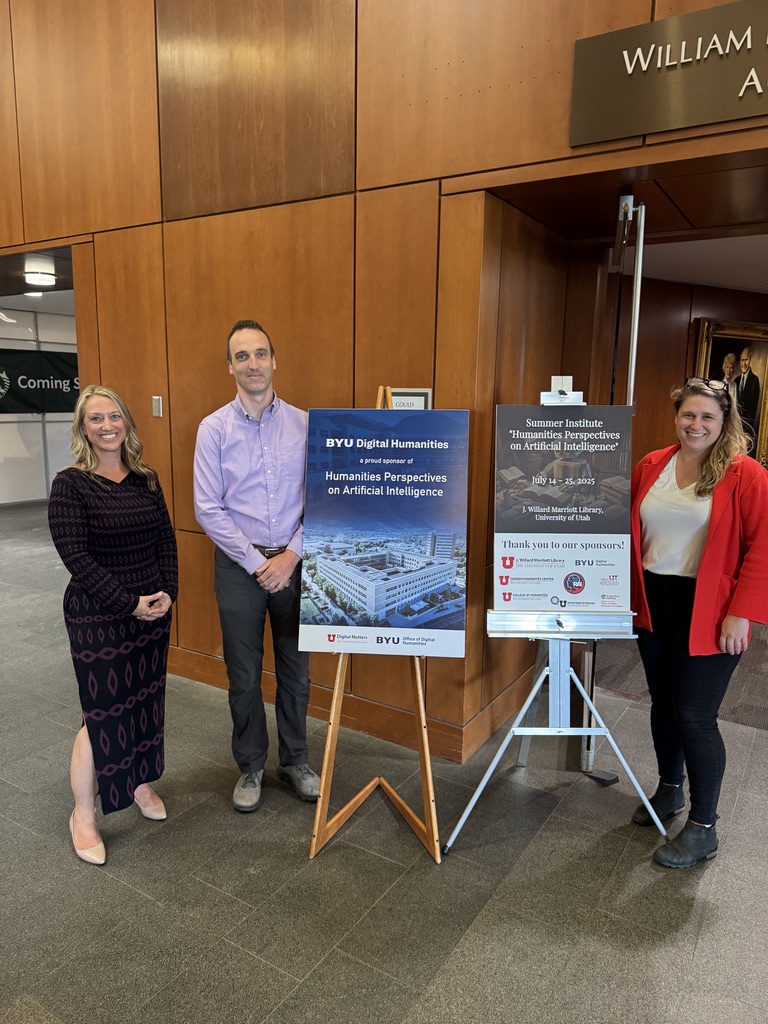

From left: Rebekah Cummings, Rob Reynolds from BYU Digital Humanities, and Lizzie Callaway

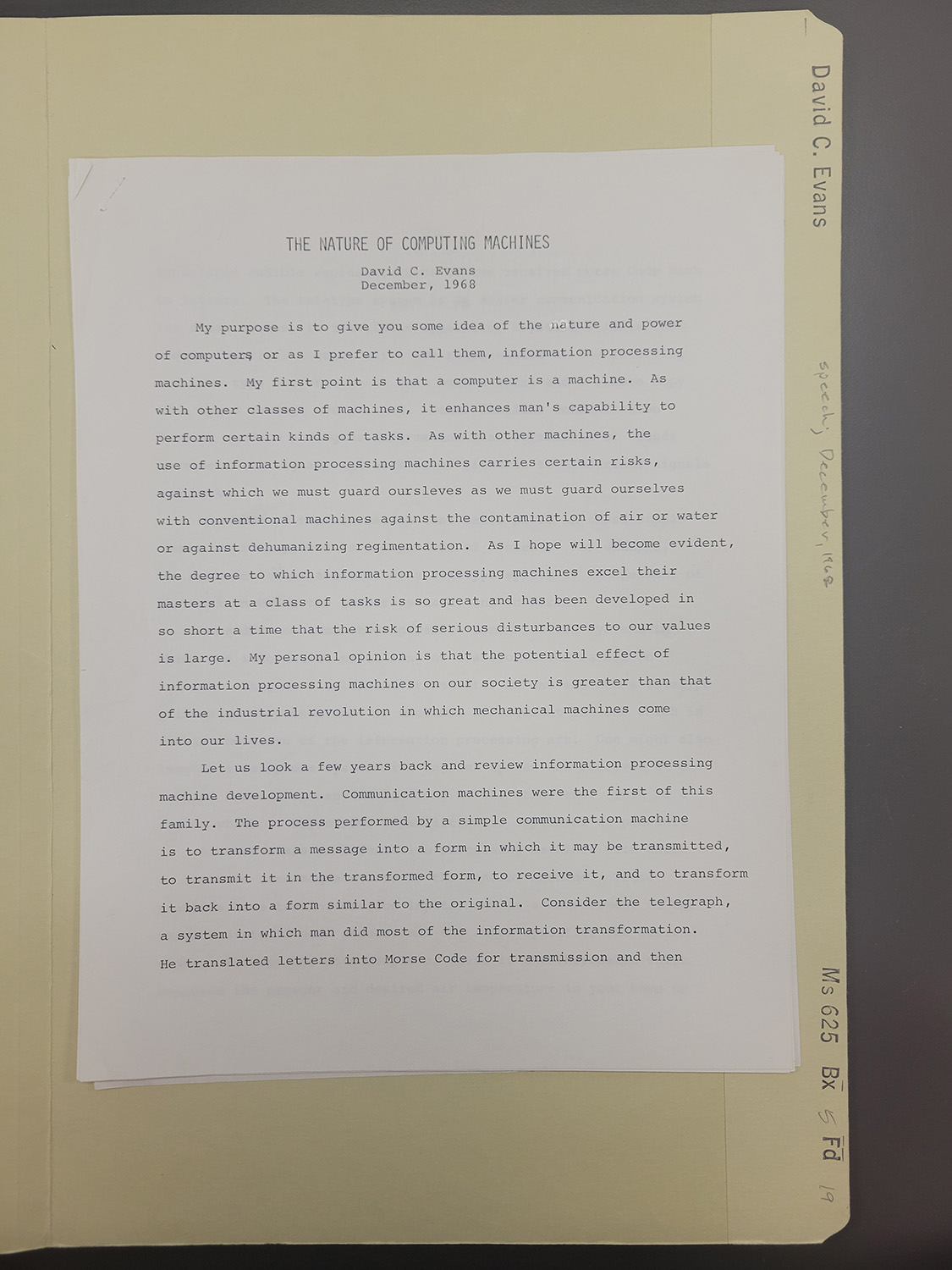

Perched at a long table in the Special Collections classroom of the J. Willard Marriott Library, I am surrounded by some 30 scholars poring over a selection of archival documents, photographs, and audio recordings from the David C. Evans papers. Evans, founder of the Computer Science department at the University of Utah and co-founder of Evans & Sutherland, left a tremendous collection to the library: business plans, company newsletters, reports pertaining to the fourth node of the then-newly established ARPANET at the U, whitepapers, and various ephemera from the heady early days of commercial computing. Unlike the relative calm of the library outside Special Collections, the classroom is humming with chatter punctuated by exclamations when someone finds an interesting item, such as this quote from a December 1968 speech:

“As with other machines, the use of information processing machines carries certain risks, against which we must guard ourselves as we must guard ourselves with conventional machines against the contamination of air or water or against dehumanizing regimentation. As I hope will become evident, the degree to which information processing machines excel their masters at a class of tasks is so great and has been developed in so short a time that the risk of serious disturbances to our values is large. My personal opinion is that the potential effect of information processing machines on our society is greater than that of the industrial revolution in which mechanical machines come into our lives.”1

Though Evans penned those thoughts for a speech delivered 57 years ago, the sentiment is prescient. The speed at which technology developed has ramped up to a frenetic pace since the 1960s. The prevalence and widespread incorporation of artificial intelligence into technologies at all levels, from the mundane to the overhyped, continues to grow.

I am in this classroom because one of the tremendous perks of my job is dropping into rooms where I otherwise would have no business being. In this case, I’ve been invited to sit in on an afternoon with the Humanities Perspectives on Artificial Intelligence Summer Institute, run by Lizzie Callaway and Rebekah Cummings. Callaway, assistant professor of English, and Cummings, associate librarian and director of the Digital Matters Lab, share an easy rapport from years of collaborating.

The institute has been a longtime dream of Callaway’s, inspired by one she attended as a participant in 2018 on the materiality of books. Her enthusiasm is palpable. Over a hurried lunch during a break on the second day of the institute, she says, “One of the things I'm most excited about is interacting with all these extremely accomplished scholars from all over the country. They come from so many different fields and so many different types of institutions and have so many different research agendas that hearing from them is what I look forward to most. I mean, I made the curriculum – that’s not new to me, so it's less exciting than how those materials are going to prompt conversations; it'll go in directions that I did not anticipate."

Callaway is not the only one to look forward to this meeting of minds. Jared McCormick, clinical assistant professor and director of graduate studies in Near Eastern Studies at New York University came to the institute “to be able to gather and spend time with a diverse set of faculty members thinking about the peril and promise of these technologies.” Comprising 27 higher education faculty and 3 high school teachers, scholars were selected through a competitive process that received more than 120 applications.

Kody Partridge, an instructor in the English department at Rowland Hall in Salt Lake City, was drawn to the institute to provide more depth of understanding for her students. She says, “Because I work with bright and creative students and I am seeing how they are engaging with AI, I wanted to be more fluent about this technology and speak to the issues that my students will need to grapple with.” The institute’s combination of expert-led discussions and hands-on application give educators like Partridge the perfect opportunity to think and experiment in a way that helps shape their pedagogy.

However, the road to pulling it off has been anything but easy. Callaway and Cummings were awarded a Summer Institute grant from the National Endowment of Humanities (NEH) last August, launching the project to bring together faculty from around the country to learn how humanities research and teaching can promote more responsible AI. They planned out a three-week institute with numerous field trips to organizations and companies using artificial intelligence in multiple ways. But on April 2nd, many NEH grants were abruptly cancelled, including this one.

Several donors immediately contacted Callaway and Cummings to make the summer institute possible. Says Cummings, “Marriott Library reached out with a substantial donation. That same day, BYU Digital Humanities reached out saying that they wanted to support the institute. Tanner Humanities Center reached out. It made Lizzie and I think that we could still do this, so we went back to our budget and found a way to make it work.” Other sponsors also stepped up to replace the sudden loss of federal funding, including the College of Humanities, Department of English, Oregon State University’s College of Liberal Arts, Utah Tech University’s College of Humanities & Social Sciences, and the One-U Responsible AI Initiative.

The institute’s schedule includes a wide variety of sessions, such as a discussion of Kurt Vonnegut’s characteristically brilliant short story EPICAC, a Q&A with journalist from the Salt Lake Tribune, and field trips to Kennecott’s copper mine and Adobe's Utah Campus. Brian Carroll, professor of communication from Berry College in Georgia, says, “Institutes like this one genuinely can be life-changing. They inform scholarly pursuits, offer new pedagogies, and perhaps most impactful of all, they form teaching and learning communities that incubate countless great ideas, questions, and approaches.” With a wide range of topics up for discussion – everything from ethical AI use for K-12 schools to the metadata that software companies can embed in their products to the environmental impacts of mining and manufacturing the physical infrastructure of AI and the energy costs associated with its widespread adoption – the experience has been rich and deep.

Participants in the institute have a variety of reasons for coming. Katherine Harris, professor of literature and digital humanities at San Jose State University, has been involved in digital humanities for years, helping to shape humanistic inquiry in digital pedagogy and policy for several California statewide and international projects. Her experience has given her a nuanced position that reflects both the promise and peril of AI. Harris reflects, “I think my concerns may be less about AI and more that higher education administrators are falling for the AI gold rush, which is being driven by tech corporations who don't have a community focus. I wish our executive administration would stop, look around, query their expert faculty, and carefully consider who to partner with in the tech industry, acting as an example to our students on how to commit to an ethics of care.”

Scholars participating in the Summer Institute gather in the Digital Matters Lab in the Marriott Library

Despite these worries, Harris also sees a great deal of promise. A scholar of literature and digital and public humanities, she is currently working on a project that uses machine reading to analyze the implications of “beauty” in 19th century literary works about the British Empire and India. She hopes “this may help us understand the complex relationship between colonizer and colonized, and perhaps, just perhaps, see how those who were colonized remade their storytelling without necessarily being erased by the British culture.” This reclamation project offers another hopeful use case for this technology. After all, as Cummings pointed out to me during one of our conversations about AI and the humanities, it is possible to imagine a world where artificial intelligence is only leveraged to do beneficial things, programmed by motivation other than pure profit.

Cummings and Callaway are particularly sensitive to the need to future-focus the institute. Back at our lunch table, Callaway chuckles, pointing out that “humanists get a bad rap for always being critical –” to which Cummings interjects, “and that’s valuable, right!” Callaway continues, “We want to ask the right questions, interrogate systems, but at the end of the day, we do need to ultimately build things that work out in the real world. I think it's important to end on hope and thinking about how, as a society, do we maximize the promises of AI and minimize the harms?”

One such change that the two would like to see is the end of Section 230, which created a carve-out to protect social media platforms and businesses from being held liable for what is posted on their platforms. Callaway argues that since algorithms are specifically developed to pick up and amplify inflammatory content in order to keep users on the apps, companies that use this technology are no longer acting as a neutral platform and therefore not entitled to the protections of Section 230. Cummings chimes in, citing an anecdote where policy makers used Polis, “an algorithm that optimized for consensus. If you could see [content with] a widespread adoption by people across the [political] aisle, that would boost it in the algorithm because in theory, it is more likely to be true. Algorithms that can build these systems would move us closer to the society we'd like to have.”

The two week institute will culminate in a public panel co-sponsored with the One-U Responsible AI (RAI) Initiative on Friday, July 25th, to take place

in the Marriott Library Gould Auditorium and stream live on Zoom. Cummings and Callaway

will be moderating a discussion with One-U RAI panelists Deanna Holroyd (distinguished

visitor) Chenglu Li, (faculty fellow) and Parisa M. Setayesh (distinguished visitor).

Members of the U community and the public are welcomed and invited to attend.

1 David C. Evans papers, speech, December 1968, Ms 625 Bx 5 Fd 19