Who Was in and Who was Out? A Conversation with U Professor Susie Porter

By Shavauna Munster

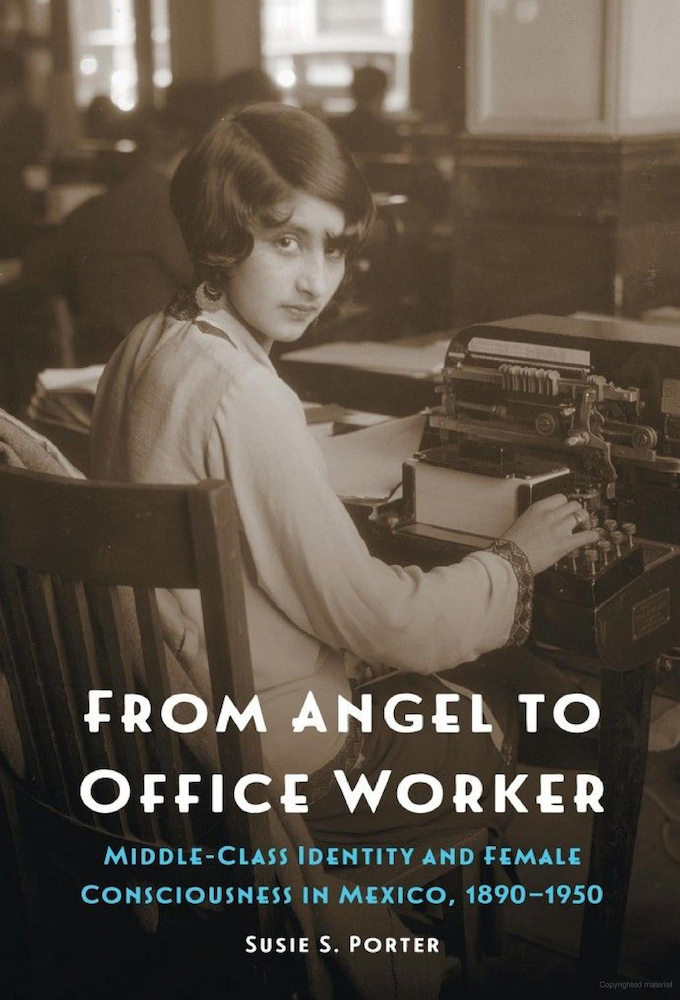

From Angel to Office Worker

While doing research for her 2003 publication, “Working Women in Mexico City,” Susie Porter, professor of history and gender studies and director of the Center for Latin American Studies at the University of Utah, had to decide who was in and who was out. Who is working class and who is not? How does this matter? Were seamstresses and secretaries included in conversations of the working class and factory workers? Many of us spend most of our days working – how does that experience inform our perceptions, our class identity and our priorities? It is these questions that led to the exploration of class and labor history in the publication of Porter’s 2018 book, “From Angel to Office Worker: Middle-Class Identity and Female Consciousness in Mexico, 1890-1950.”

“For me it is, in part, a political project, to point out that most of us are workers,” said Porter whose book takes us to a moment of transition in society and women’s perception of what it meant to be a woman. “I might be a professor, someone else might be a high-level manager in a company, but we are all workers.”

In the latter half of the 19th century, women in Mexico worked largely as seamstresses, allowing them to remain at home – a hallmark of middle-class respectability. As businesses and government services expanded, entry-level office positions attracted women looking to support themselves, their families, and to support/maintain middle-class consumption. While women leaving the private sphere and entering the workforce led to significant backlash that questioned the morality of female workplace participation, it also allowed women to expand their consciousness, a primary argument of Porter’s book. “I use the word consciousness to talk more broadly about women’s rights as a shift in women’s sense of themselves and what they needed in order to flourish at home and in society that might well go beyond suffrage. At this time, women are pushing the boundaries of what they can do in the workplace. Equal pay for equal work, transparency in the workplace, they start to speak back to the idea that women are first mothers,” said Porter.

Commercial schools prepared women for occupations that could combine both the public sphere and domesticity – offering lessons in home economics interspersed with lessons in boundary-pushing topics like birth control. Public debates erupted over women’s dress and behavior in the government offices, attacking low necklines and short haircuts. In response, women argued that if they had to wear uniforms, so too should the men and redirected the conversation to more important issues such as women’s rights to vote.

Although government positions were associated with middle-class identity, many women working in offices earned less than half of that earned by carpenters and mechanics. However, government office jobs were associated with middle-class status because they required some form of education and were performed in an office setting. Throughout the book, Porter establishes this connection of working- and middle-class activism in the labor movement and argues that the women’s movement was also a labor movement. “For example, the post office was one of the fastest growing and most profitable office in the Mexican bureaucracy in the early 20th century because offices are writing letters and contracts. They hired women to be letter sorters and the expansion of the bureaucracy was on the backs of hiring women as cheap labor. The revolution in 1917 led to another expansion of the government – education and division of labor – for a while there is a huge increase in the number of women working in these offices.”

Discussing the impact of her research, Porter notes that, “My contribution to the historiography is to point out the ways the women’s movement was not limited to women of privilege demanding the vote. What I argue is that this shift in women’s workforce participation put women in a position to have an education, to be able to speak out, and draw on their workplace experiences and shared condition. The women’s movement became a movement for equal pay for equal work, recognition of women’s seniority at work and a demand for day care so they could balance their responsibilities at home and in the workplace”

Porter’s book is the winner of the 2019 Thomas McGann Award for best publication in Latin American Studies and is a major contribution to modern Mexican history. It begs that we ask new questions about labor movements, women’s rights and politics while providing an argument that is both captivating and compelling.